Image: International Monetary Fund

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) have been, and continue to be, a huge problem for developing countries, especially. They hinder countries’ ability to meet the UN sustainable development goals, because they undermine the fiscal systems which are in place to collect government revenue, and reduce the amount of funds available for development and the provision of public services.

The illicit money stems from corruption, dodgy tax and commercial transactions, fraud, criminal activity, or illegal markets, among others. Corruption is a particular risk, because not only does it generate illicit funds and exacerbate the likelihood of IFFs, but it also undermines the very institutions that are responsible for detecting, investigating, and prosecuting those IFFs.

And with a large part of the outgoing capital ending up in developed countries – often with the full knowledge of authorities there – it becomes difficult, if not nigh impossible, to recoup it, while criminals are as likely as not to get away with their misdeeds.

Transparency International (TI) recently undertook an assessment of 78 such cases involving IFFs from Africa, many of which had made it to courts around the world. Using data available from court records, leaked information, investigative reports and other public sources, says the organisation, it uncovered not only where stolen or hidden funds from Africa end up, but also the mechanisms and tools used to move them around and hide them.

“Our analysis is based on cases of corruption confirmed by court decisions, as well as credible allegations of corruption and hiding of wealth offshore. Our findings reveal the destinations, methods, and assets most commonly used by corrupt actors to launder stolen money. They also highlight the urgent need for action to close these loopholes.”

Out of just those 78 cases, TI found over US$3.7-billion in corruption-linked African assets hidden in 74 separate jurisdictions, the top culprits of which are wealthy nations.

“This figure likely represents the tip of the iceberg, as it only includes assets identifiable through public sources.”

Where does the money go?

TI’s findings correspond with those of other organisations, such as the Tax Justice Network, which work to banish secrecy and fight IFFs. The organisation found that fully 80% of assets ended up overseas, often far from where the corruption originally occurred.

Anonymous companies, bank accounts, and real estate were favoured by criminals as tools through which to dispose of dirty money, with the intention of putting the assets beyond the reach of the law.

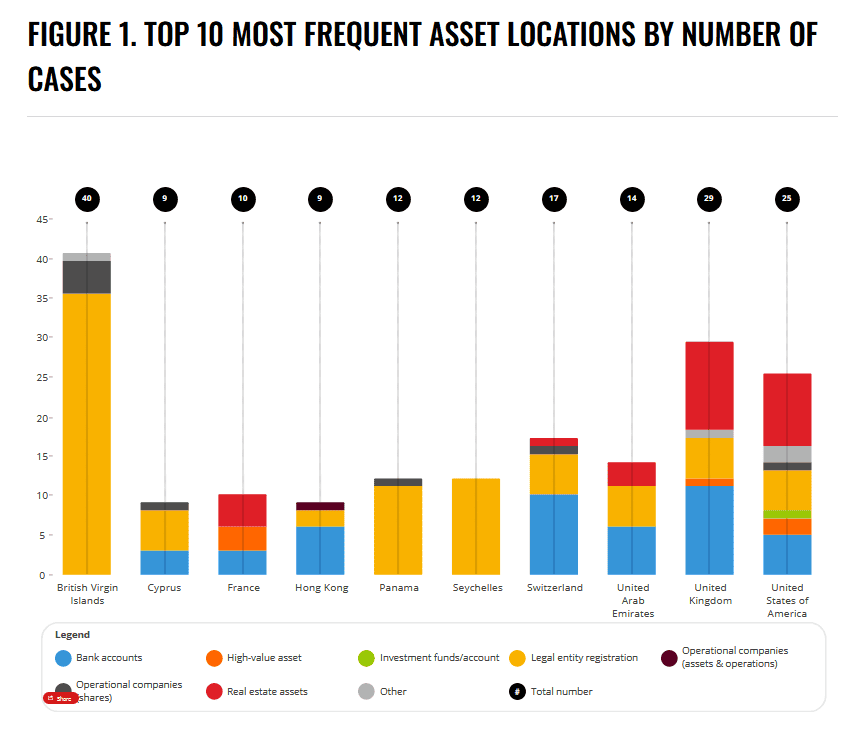

TI identified the British Virgin Islands, Panama, and Seychelles as the top hubs for incorporating companies with the aim of concealing assets and stolen funds. France, the UK, the UAE, and the US were the preferred locations for purchasing properties connected to suspicious activities, while Hong Kong, Switzerland, the UK, the UAE, and the US were key destinations for bank accounts used to pay bribes and move or store dirty funds.

These wealthy countries have been abetting criminals for years, as scandalous expositions such as the Panama Papers, the Swiss Leaks, the Pandora Papers, and Dubai Uncovered have revealed – among numerous other data troves leaked to the public.

In 85% of cases, says TI, companies and trusts were used to obscure the ownership of assets. “Often, complex cross-border corporate structures or multiple shell companies were used to distance corrupt individuals – and their dirty funds – from the asset in question.”

The use of secrecy jurisdictions to register companies is important to prevent information on the real, or beneficial owners from coming to light.

Real estate in countries like the UK, US, and France, where criminals exploit regulatory loopholes that enable them to hide their ownership status, is a popular choice – TI identified 121 properties worth at least US$560-million, with most located abroad and often owned via companies or trusts.

“In France, foreign companies can purchase real estate without declaring their true owners, a gap that the EU’s 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive aims to close,” says TI, adding that in the UK, ownership of real estate can be hidden through offshore companies held by trusts, and in the US, non-financial enablers dealing in real estate are not required to do customer due diligence or even file suspicious transaction reports.

The way forward

To effectively combat cross-border corruption and the laundering of stolen funds, says TI, all stakeholders must play their part. “Governments, professionals in the financial and non-financial sectors, and international bodies must take urgent action.”

TI recommends the following measures:

- Enhance transparency in asset ownership by requiring all assets to be registered with a government authority, making those registers available to journalists, civil society, and the public, and guaranteeing access to that information. Beneficial ownership registers should immediately be set up in countries where there are none.

- Regulate and supervise enablers of corruption by establishing mandatory anti-money laundering rules that will apply to all professionals in the financial and non-financial sectors, closely scrutinising gatekeeper professions, and imposing severe consequences on those found guilty of criminal activities in this regard.

- Strengthen mechanisms for tracing, seizing, confiscating, and returning assets by ensuring that data on assets is used to identify risk patterns and gaps in legislation, and inform supervisory and enforcement efforts. Financial intelligence units should receive more funding and support, and there should be civil and criminal mechanisms in place to seize and confiscate assets, as well as channels through which to repatriate such assets.