This piece is extracted from Corruption Watch’s 2021 annual report. For more information, click here.

By Moepeng Talane

First published on Daily Maverick/Maverick Citizen

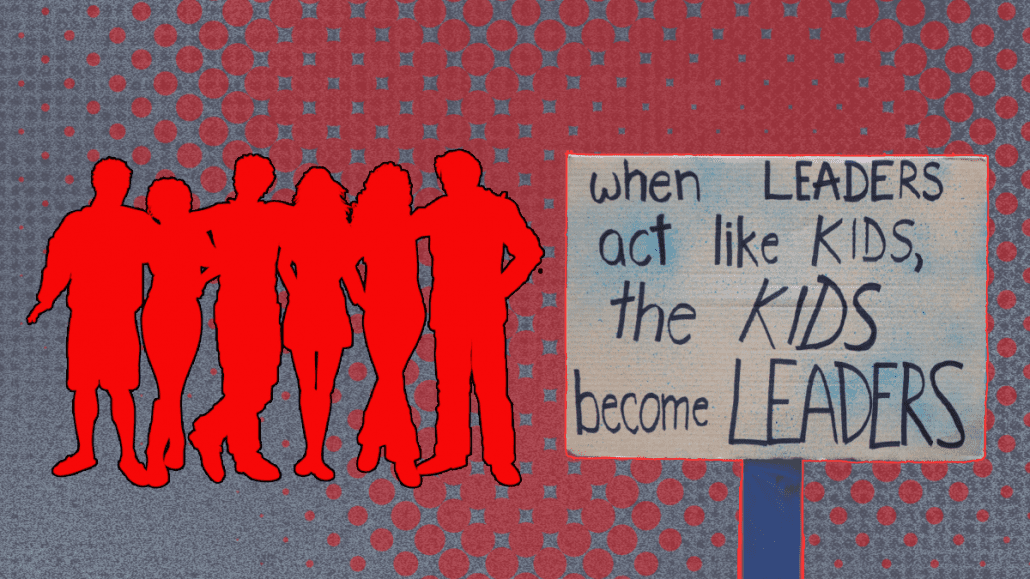

South Africa’s dynamic history has a strong narrative of youth activism that transcended the dark days of a violent apartheid system and the accompanying restrictions. From the young pupils who were attacked by the security police in the 1976 Soweto uprising, to the countless others across the country who used literature and other art forms to expose the realities of the time, the country has never been short of activists.

Fast forward to present-day South Africa, and you will realise that it is young people who continue to grapple with much of society’s ills. More organised, more informed and more vocal than ever on politics, crime, gender-based violence, and unemployment and education, among other issues, the social justice landscape is rich with the insights of young minds who want change for South Africa at any cost.

When asked in an interview carried in the Corruption Watch annual report, to be released on 31 March, former executive director of Corruption Watch (CW) David Lewis said the one thing that inspired him to persevere in the early days of the organisation was the rate at which it attracted young people who were sincerely committed to its cause.

Heeding the call

Social justice is a calling many take up with optimism that they can make a positive change in the world. For CW’s young activists, inspiration comes from knowing that they make a small difference, but a difference nonetheless, that will leave a mark on our democracy.

Researcher Melusi Ncala says he has always known that he was wired differently and could make waves by just engaging his mind. “I recall one of my high school teachers describing me as an inquisitive person and that stuck with me. It would be this label, which I, of course, thought about ad nauseam, that helped me in my undergraduate and postgraduate studies at university.”

His job is not to merely collate and analyse all the data that CW works with, but to help build a narrative that there is no dignity in engaging in corrupt practices.

His inquisitive mind remains intact and has not stopped questioning the status quo. “I constantly self-reflect and wonder about the world I live in. Why are we so troubled as a people? Where do these problems come from? Am I adding to the hardships and if so, how can I contribute positively to people’s lives?”

Colleague and youth campaign coordinator Mzwandile Banjathwa shares the same spirit. His background is in youth politics, and his passion for our young people is easily identifiable in the way he engages them on a host of topics in his everyday work. He believes that with the indomitable spirit of the youth firmly in place, the fight against corruption can be won.

“Corruption Watch has brought together a group of diverse young people that we refer to as the Youth Forum, giving them a platform to engage in corruption-related matters and help come up with innovative means of fighting the scourge,” said Banjathwa.

Behavioural change for the youth means moving from not only the traditional challenges as a society, but also the traditional solutions. “Youth community engagement provides an opportunity for Corruption Watch to engage with a wider demographic of young people in their own communities … forum members choose their own topic to engage on, CW then assists in developing content and logistics.”

It is clearly a case of the youth deciding what works for them and engaging in debates that find solutions from their contemporaries.

Leave no-one behind

But doesn’t this mean that challenges in the less diverse communities do not get the same attention? Surely rural youth, too, must have a voice on how their socio-economic circumstances would improve in a corruption-free South Africa.

Enter Mashudu Masutha, one of CW’s legal researchers and project manager for its mining-related work. The excitement with which she speaks of the two projects under her watch — the Mining for Sustainable Development (M4SD) Project and the Mining Royalties Programme (MRP) — will cause anyone to stop and listen.

The M4SD and the MRP are two of the organisation’s flagship projects, and have taken Masutha to some of the country’s most vulnerable communities while positioning CW as an expert participant in the two related topics.

The two projects highlight the plight of communities that have lived on land used for mining activities. Their case for development and compensation is often overlooked by mining companies, government, or both. By and large, these are communities that suffer neglect because the legitimate structures that should be protecting their rights in the public sector are misunderstood or even overridden, in some cases because of abuse of power.

“We wanted to respond to that call and commit to creating change for communities that lived in very challenging conditions with concerning limitations, and help them to exercise their Constitutional rights,” explains Masutha.

“Our commitment was emphatic. One of the highlights in the early days of the mining work was a five-day series of extensive community engagements with the Bakwena ba Mogopa traditional community in the North West. The CW team, which included researchers, attorneys, investigators and media experts, met with more than 100 community members each day in different villages, all expressing their concern at the rate of corruption in the community.”

She adds: “During these engagements, there was a palpable sense from the community that CW was going to bring change, that with our organisational mandate we would be able to provide answers to the many questions around where community funds have disappeared to, and how the law and activism can help to bring accountability and transparency.

“I can confidently say that as a team, we all felt an almost personal responsibility to meet this expectation, and we delivered.”

Policing the police

Other community work we have done as CW relates to our police campaign. Here, we sought to get insight from different communities around the country on what service delivery from the South African Police Service looks like. The feedback was seldom positive and reflected a desperation from communities that wanted protection and accountability from the police officers who work in their areas.

What developed from these engagements was a need to empower communities and place a tool in their hands that enables them to do just that — make their police stations and the police leadership in their areas, accountable. This is when the concept of the Veza tool came to light. Kavisha Pillay, CW’s head of stakeholder relations, spearheaded this first of its kind innovation.

“In 2017/18, the campaigns team began a series of roadshows across the country where we would engage communities on their experiences of corruption, particularly in relation to healthcare, schools and policing. Our engagements on policing always revealed a disturbing trend of abuse that vulnerable communities were/are subject to,” she says.

Each team member was tasked with looking at local, regional and international approaches to deal with some of the experiences that were being reported to CW. This became the basis for the Veza tool.

“We took global and local examples and developed a site that we hope will improve the power imbalance that exists between the public and the police. In the first year since launching Veza, over 12,000 people have accessed it, we received 100 + reports of police corruption, 450+ individuals rated their police stations, and we received 35+ nominations of ethical cops. We are still in a pilot phase, and we hope to one day anchor the Veza tool as a central site on matters related to policing.”

CW’s youth changing the world

Great strides are made in our work as CW when the young activists in our team go out into the world to seek answers. Their ask in return is a world that changes, at least for the few individuals they get to encounter in their everyday work, so that they too can claim a place in a just society.

Ncala puts into perspective why activists thrive in the task of helping others: “Research has given me an opportunity to look at issues from a number of angles guided by the answers emanating from questions that I think about as I attempt to problem-solve.

“Applying it to the theme of corruption, as a social justice issue, it has opened my eyes to the depth of people’s depravity and how politics is simply about self-interests. I have had to refocus my activism in such a way that I address issues holistically through understanding the intersectionality between corruption and other socio-political areas such as race, class and gender.”

For Banjathwa, it’s the empowered feeling that he gets from voicing the struggles of others, that matters. “I’m able to see and engage the complexities brought forth by corruption and I also have the unique opportunity to articulate it with the authority entrusted to us by our courageous whistle-blowers.”