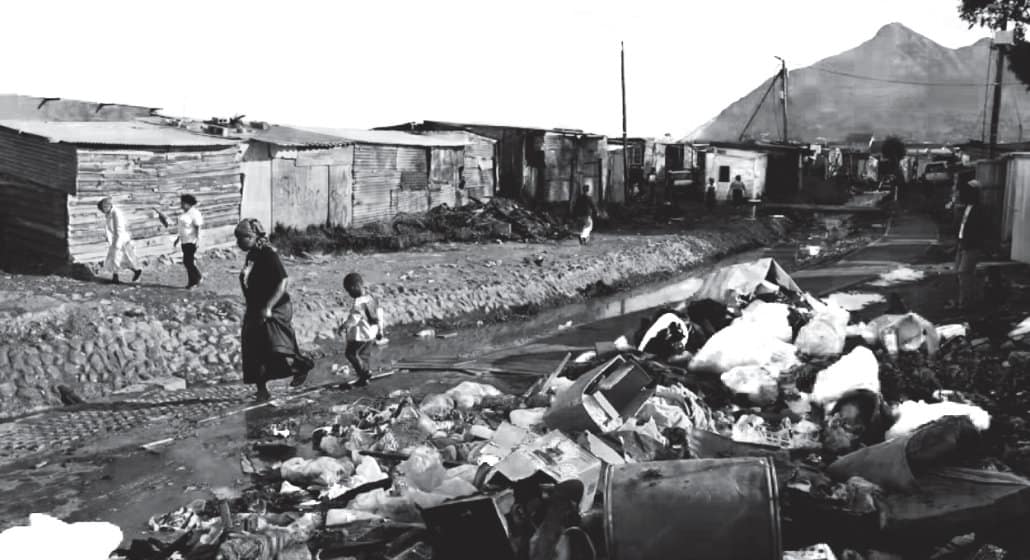

Image: EFE-EPA/Nic Bothma

By Marcel Nagar

First published on The Conversation: Africa

A public policy works well if it’s a good policy and if it’s carried out well. Politicians make policy and specialist bureaucrats in the public service carry it out. These appointed officials are supposed to follow a strict professional and ethical code of conduct.

Over the past 30 years, South Africa has not had this kind of public service. Public servants have not been able to put into practice the policies designed to end poverty, inequality, and unemployment.

My research has centred on the intersection between bureaucracy, democracy and development in Africa under the conceptual banner of the developmental state. A developmental state is typically that in which the state plays a dominant role in driving rapid economic growth and development to improve the welfare of the population.

I have also examined South Africa’s efforts at constructing a developmental state in the aftermath of COVID-19, and developmental local government. Sadly, this review shows that the country’s public service is largely dysfunctional.

A change in political leadership would make little difference to development without a major reform of the public service.

In my view the public service has failed to uphold the values and principles governing its operations as outlined in the Constitution. It has not done what section 195 of the Constitution requires:

- maintain professional ethics

- use resources in an economically efficient way

- operate in an impartial and equitable manner

- adopt a development-oriented vision and approach

- strive for inclusivity, accountability and transparency.

1. Failure to maintain a standard of professional ethics

South Africa’s public service has failed to perform ethically in its public duties and its internal operations.

This shows in the high prevalence of corruption – bribery, embezzlement, fraud, and conflict of interest. Citizens are all too familiar with the term “state capture”, referring to entrenched corruption in the public sector.

The 2018 judicial commission into state capture, that probed corruption in the public sector, found evidence of a network of persons outside and inside government acting illegally and unethically in furtherance of state capture.

Some ordinary bureaucrats such as traffic and police officials are corrupt too. This contributes to lawlessness, disorder, and crime.

2. Failure to use resources in an economically efficient way

Maladministration, typically the mismanagement of public resources, has been a growing concern. The state capture commission or Zondo commission found that the primary way that money has been extracted from state institutions has been through procurement.

Public procurement abuses were most rife among state-owned enterprises such as the power utility Eskom, the transport parastatal Transnet and South Africa’s largest manufacturer of defence equipment, Denel.

State money and resources have also been squandered through unauthorised, irregular, fruitless and wasteful spending. This is often a result of

- inadequate skills and capacity

- governance failures

- lack of accountability and consequence management

- poor financial management

- inadequate financial controls.

According to the Auditor-General, unauthorised expenditure by national and provincial government departments totalled R4.59-billion (US$247-million) in the 2022-2023 financial year. Irregular expenditure was R63.37-billion (US$3.38-billion). The relevant accounting officers and authorities manage an estimated collective expenditure budget of R3.10-trillion (US$167-billion).

3. Failure to operate impartially and equitably

The public service has failed to remain politically neutral. Civil servants should be impartial and objective, and act in the best interest of the public. Section 197 of the Constitution says that no employee of the public service may be favoured or prejudiced only because that person supports a particular political party or cause.

The governing African National Congress’s policy of cadre deployment has brought politics into the public service. The policy involves placing party loyalists in prominent positions in the civil service. It thwarts the building of an impartial and independent public service.

The Zondo commission found that cadre deployment contravened the Public Service Act.

Senior public servants have been appointed because of their loyalty to the party rather than merit and technical competence. Consequently, unqualified and incompetent personnel can be found at the highest level of management.

In 2021, 35% of senior managers did not have the requisite qualifications for their positions.

4. Failure to adopt a development-oriented vision and approach

For an aspiring developmental state such as South Africa, success lies in providing basic public goods and services. Access to housing, infrastructure, healthcare, and education is vital to create an environment for inclusive economic growth.

The state is struggling to provide these basic goods and services. For example, every South African has been affected (directly or indirectly) by power outages since 2007. Many rural communities still do not have access to water and sanitation systems, a basic human right.

Growing discontent can be seen in the high number of service delivery protests. There were about 3 000 between 2004 and 2019, rising to 2 455 from July to September 2022.

A 2023 survey by Afrobarometer, the independent pan-African survey network, found that only 28% of respondents were satisfied with the provision of water and sanitation. Only 12% were satisfied with access to reliable electricity and 11% with government’s efforts at reducing crime.

5. Failure to strive for inclusivity, accountability and transparency

Since the end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa has sought to become an inclusive, accountable and transparent state.

To this end, the government has created ways to include citizens in its governance processes and in holding officials accountable. These include public hearings, public access to parliamentary portfolio committee meetings and local government development planning processes, and ward committees.

But the politicisation of the public service has made it more challenging to promote public accountability and transparency. Policies such as cadre deployment have eroded the integrity of the public service by blurring the lines and responsibilities between (elected) politicians and (appointed) public servants. It becomes difficult to know where to assign the blame for service delivery failures, maladministration, and corruption.

Looking forward

The government appears to be finally taking the idea of a professional public service more seriously. In 2022, it published a framework for the professionalisation of the public sector which aims to build a state that better serves our people, that is insulated from undue political interference and where appointments are made based on merit.

The policy seeks to ensure that the public service is staffed by “professional, skilled, selfless, and honest” civil servants who are committed to upholding the values enshrined in the constitution. It remains to be seen whether this can be achieved while the ruling party ANC remains committed to cadre deployment.

With general elections on 29 May, it is important to note that new political leadership would not necessarily bring about instant change in people’s socioeconomic conditions.

Not when the public service is dysfunctional. This is true not only at the national level, but, more importantly, at the local government level, which has the task of delivering basic services to the poorest of the poor.

Dr Marcel Nagar is a senior postdoctoral research fellow at the NRF SARChI Chair: African Diplomacy and Foreign Policy at the University of Johannesburg, where she obtained her doctoral degree in political science in 2019. Her research interests include African politics, South African politics, South African public policy and administration, international political economy, and the broader debates surrounding the democratic developmental state.