|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index (GI) is an initiative of Transparency Internal UK’s Defence and Security Programme. The index assesses the existence, effectiveness, and enforcement of institutional and informal controls in the management of corruption in defence and security institutions. The organisation made its Africa report available online in January – it will be officially launched in South Africa tomorrow.

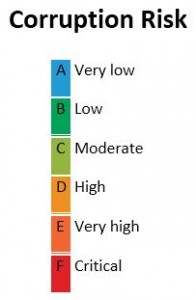

To compile the index, TI gathers evidence from a wide variety of open-access sources and interviews across 77 indicators, to provide governments with detailed assessments of the integrity of their defence institutions. Each country receives a risk score from A (very low) to F (critical).

This report is the fifth in the GI series and provides the country risk rankings derived from data for 47 African countries. South Africa is one of a few chapters that actively contributed to the index.

TI UK also publishes the Defence Companies’ Anti-Corruption index.

Download the 2015 Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index.

Download the South Africa summary.

Corruption in defence a feature of the continent

Africa as a continent is not a shining light in the domain of defence anti-corruption. The best scores fell into the D band – high risk – and only seven out of 47 countries managed this. South Africa is one of them.

The rest of the countries surveyed fell into the E band (very high risk) or the F band (critical risk), with 20 countries in each band. Not all African countries were surveyed.

Countries’ placement into bands depends on their scores from a set of 77 questions – for each question, the government receives a score from 0 (bad) to 4 (good). The overall marks determine the band. The questions fall into five broader areas – political (South Africa scored 53%), financial (50%), personnel (56%), operations (30%) and procurement risk (43%). South Africa’s mediocre scores for political and personnel risks fell into band C, while scores for procurement (band D) and operations (band E) were disappointing.

South Africa is one of the 16% of countries worldwide that falls into the D band overall. This puts the country at high risk for corruption in the defence and security sector. The results mirror those of the recent GI for G20 countries, which was released in November.

TI UK identified three main areas of concern for South Africa – the independence of anti-corruption investigations and enforcement bodies; protection for whistleblowers; and classified procurement spending.

In the first area, TI singled out the Seriti Commission of Inquiry into allegations of fraud and corruption in the arms deal. The commission’s establishment was initially viewed as a positive move, but later allegations of bias, together with numerous high-profile resignations of staff members and participants, cast doubt on its effectiveness.

“How independent the commission’s findings prove to be and how conclusions are handled by President Jacob Zuma, himself implicated in the procurement scandal, will be an indicator of the strength of South Africa’s approach to anti-corruption,” said TI.

The organisation recommended that the South African government allow investigation and oversight agencies to pursue their work impartially and with sufficient resources, to maintain public trust in the integrity of the defence sector.

In terms of whistleblower protection, TI noted concerns that ratification of the Protection of Sate Information Bill (aka the secrecy bill) would make it much more difficult to access information, reduce protection for whistleblowers, and heighten corruption risks. TI recommended that whistleblowing be actively encouraged by the government, and that the bill be referred for review.

TI mentioned that transparency and accountability in South African defence procurement is severely limited by secret budgets. The organisation recommended that the government ensures the establishment of mandatory provisions for oversight of all secret expenditure by an internal and external audit function and an appropriate parliamentary committee. The government should also clarify what percentage of defence and security expenditure in the budget year is dedicated to spending on secret items.

Africa needs to tidy up its act

Although there have been notable improvements – such as the professionalisation of armed forces in Ghana and Zambia – the risk of corruption in this space remains high across the continent, the GI found. The situation is worsened by an increase in military spending in Africa – in 2014 the 47 African countries under survey spent around US$40-billion. Although this comprises only around .02% of global military spending, it represents a sizeable portion of African GDP, in some cases over 10%.

Furthermore, there is little to no transparency on how this money is spent. Coupled with limited oversight, the potential for corruption is great.

The overall defence corruption picture in Africa is mixed, although generally negative, with state corruption risks ranging from D to F, representing “high” to “critical risks”.

TI noted several themes across the continent:

- Defence spending is rising, but institutional capacity is lagging. In many cases oversight functions exist in the form of anti-corruption bodies, audit functions, and/or parliamentary committees, but defence institutions are largely exempt from scrutiny.

- Increases in defence spending are not necessarily enhancing state security. Too often procurement decisions are taken with little reference to strategic requirements, military effectiveness is eroded by poor controls on personal, while forces are repurposed for commercial ends.

- Corruption is undermining public trust in the government and the armed forces, as well as posing a major threat to the success of operations. In fact, the index found that in only Rwanda and Tunisia do the public believe there is a clear commitment from the defence establishment to tackle corruption.

- And finally, international arms exporters from the US, China and Russia, among others, are profiting from conflict and insecurity.

While the consequences of corruption are well known and documented, said TI, too many African leaders are ignoring the real problems facing their countries. Instead, they’re building up their patronage networks and using taxpayer money to buy the loyalty of those who carry the guns in their country.

“Though paying lip service to issues of corruption, leaders of many African states have failed to redress institutionalised corruption risks, especially in their defence sectors.”

In many cases oversight functions exist in the form of anti-corruption bodies, audit functions, and/or parliamentary committees, but defence institutions tend to be exempt from scrutiny. “By treating the defence sector as exceptional, its efficiency has been undermined.”

The GI shows that there is no country in Africa whose defence sector is not vulnerable to corruption. In the end, corrupt governments are the architects of their own security crises, TI concluded.