|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

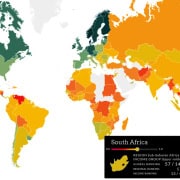

These days South Africa – and let’s be fair, many other countries – is almost expected to make mediocre showings on various global governance-related indices. The Corruption Perceptions Index is one. The World Justice Project’s (WJP) Rule of Law index is another.

The WJP Rule of Law index measures the practice of the rule of law, based on the experiences and perceptions of the general public and in-country legal practitioners and experts in 139 countries and jurisdictions.

The WJP defines rule of law according to four universal principles:

- Accountability – the government as well as private actors are accountable under the law;

- Just Law – the law is clear, publicised, and stable and is applied evenly. It ensures human rights as well as property, contract, and procedural rights;

- Open Government – the processes by which the law is adopted, administered, adjudicated, and enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient;

- Accessible and Impartial Justice – timely justice is delivered by competent, ethical, and independent representatives and neutrals who are accessible, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve.

It is clear, therefore, that the rule of law encompasses not only adherence to the law, but also the correct and just development, enforcement and delivery of the law.

“To be effective, rule of law development requires clarity about the fundamental features that define the rule of law, as well as an adequate basis for its evaluation and measurement,” says the WJP, and to this end the index measures eight relevant factors: Constraints on Government Powers, Absence of Corruption, Open Government, Fundamental Rights, Order and Security, Regulatory Enforcement, Civil Justice, and Criminal Justice. These eight main factors are divided into 44 sub-factors.

The first four factors measure whether the law imposes limits on the exercise of power by the state and its agents, and also individuals and private entities. The last four factors measure whether the state imposes limits on the actions of members of society and fulfils its basic duties towards the people by serving public interest, protecting people from violence, and providing access for everyone to grievance and dispute settlement mechanisms.

Download the 2021 index.

Download South Africa’s 2021 information.

Global decline

The 2021 index shows that for the fourth year in a row, more countries declined than improved in overall rule of law performance, which is measured on a scale of zero to 1, where zero indicates no adherence to the rule of law and 1 indicates full adherence. This trend has become more widespread over the last three years.

Over the last year, 74.2% of countries experienced declines in rule of law performance and 25.8% improved. The 74.2% which declined account for 84.7% of the world’s population, or approximately 6.5-billion people. For the second consecutive year, the declines were widespread and seen all over the world. In every region, a majority of countries slipped backward or remained unchanged in their overall rule of law performance.

Denmark, Norway, and Finland were at the top in 2021. Venezuela RB, Cambodia, and Democratic Republic of the Congo had the lowest scores of all – the same as in 2020.

The countries with the biggest improvement in rule of law in the past year were Uzbekistan (4.1%), Moldova (3.2%), and Mongolia (2.0%). The countries with the biggest decline in rule of law in the past year were Belarus (-7.5%) and Myanmar (-6.3%). Nigeria, Nicaragua, Kyrgyz Republic, and Argentina tied for the third biggest decline (-3.7%)

South Africa mediocre yet again

In 2021 South Africa scored 0.58, a marginal decline from last year’s 0.59. In fact, these two figures are the country’s lowest and highest achievements, indicating that not much has changed in seven years.

The country’s rank in 2021 was 52, and 45 and 47 in the two preceding years respectively. In sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa was ranked fifth out of 33 countries. The top four were Rwanda (1), Namibia (2), Mauritius (3) and Botswana (4). Rwanda improved by two positions, while Namibia and Botswana declined by two and one rankings respectively, while Mauritius did not move.

South Africa did fare better than some big economies around the world, notably its Brics partners Brazil (score of 0.50), China (0.47), Russia (0.46), and India (0.50), as well as the majority of its sub-Saharan fellows. However, given the consistently low scores of the latter, with all but nine scoring below 0.50, this should hardly be a source of pride.

In terms of the indicators, it will come as no surprise that Absence of Corruption was the country’s weakest link with a score of 0.48, while Fundamental Rights at 0.64 was where it scored the best. In the former category, the legislature was perceived to be the biggest problem, followed by the executive, the police/military, and the judiciary – these were the only choices.

No leadership example of respect for the rule of law

When it comes to the inculcation of respect for the rule of law, many will bemoan the lack of it in our country.

South African citizens, on a daily basis, see their leaders at all levels of government and in the private sector not only breaking the law, but blithely getting away with it, while citizens have to face the music. A recent case in point is that of Sibongile Mani, a university student whose bank account was one day enriched – not through her doing – by R14-million, instead of R1 400. She did not report the incident and spent close to a million rands of the money before the irregularity was discovered and the balance recouped. In February 2022 she was found guilty of theft and sentenced to five years in jail with no option of a fine.

In contrast we have Bathabile Dlamini, former social development minister who oversaw the debacle that was the social grants distribution scandal a few years ago. In March 2022 a court of law found her guilty of a serious crime – that of perjury, which is the deliberate act of telling an untruth before the law, having taken an oath to be truthful. She was sentenced to a fine of R200 000 or four years in jail. Naturally she chose the fine. Dlamini is no stranger to the inside of a court, having pleaded guilty in 2006 to fraud charges relating to the abuse of parliamentary travel vouchers – the amount she got away with was R254 000. Her career should have ended there – but it didn’t. Instead, not long after, she was elected to the ANC’s national executive committee, with accountability – the first universal principle of the rule of law – nowhere to be seen.

This seeming disparity in the justice system’s treatment of two women – one a young student, the other a powerful politician – is a violation of the first and second principles of the rule of law, and it is symbolic of the larger long-standing situation in the country. It is also one of several reasons why many South Africans have little faith in the law.

Why is rule of law so important?

The rule of law affects all of us in our everyday lives, said the WJC. Although we may not be aware of it, the rule of law is profoundly important – and not just for lawyers or judges. Every sector of society is a stakeholder in the rule of law. Below are a few examples, as provided in the WJC report:

Business Environment

Imagine an investor seeking to commit resources abroad. She would probably think twice before investing in a country where corruption is rampant, property rights are ill-defined, and contracts are difficult to enforce. Uneven enforcement of regulations, corruption, insecure property rights, and ineffective means to settle disputes undermine legitimate business and deter both domestic and foreign investment.

Public Works

Consider the bridges, roads, or runways we traverse daily – or the offices and buildings in which we live, work, and play. What would happen if building codes governing design and safety were not enforced? What if government officials and contractors used low-quality materials to pocket the surplus? Weak regulatory enforcement and corruption decrease the security of physical infrastructure and waste scarce resources, which are essential to a thriving economy.

Public Health and Environment

Consider the implications of pollution, wildlife poaching, and deforestation for public health and the environment. What would happen if a company were pouring harmful chemicals into a river in a highly populated area and the environmental inspector ignored these actions in exchange for a bribe? Adherence to the rule of law is essential to holding governments, businesses, civil society organisations, and communities accountable for protecting public health and the environment.