That there is corruption in South African prisons is no secret – but the actual extent of it might never be known for sure.

A few recent incidents taken up in the media give us a hint – issues at Leeuhof Prison, in Vereeniging, Gauteng, which were revealed in June, were just one example. "Gangsters and wardens are still smuggling dagga, heroin and crack cocaine; criminals are still hiding knives and sharpened objects in the 'mineshaft' and inmates are stockpiling condoms for sex," the City Press reported in a follow-up article to its exposé of the appalling conditions in that institution.

Then, in July, media carried reports of five correctional services officials from Worcester Prison, who were arrested for allegedly helping a gang culture to thrive inside the prison. They are suspected of contravening the Prevention of Organised Crime Act, taking part in drug smuggling and other crimes on the inside, and working with the Junior Cisko Yakkies gang. This gang, and others in the area, has been linked to a network of street and jailed criminals.

Simphiwe Xako, a spokesperson for the Department of Correctional Services (DCS), said at the time: "It's quite sad and it's shocking what happened because as correctional officials, we are called upon by the Constitution and the law to make sure South Africa is a safe place."

At the beginning of the year, newspapers were buzzing with reports of a video showing two of the so-called Waterkloof Four – each sentenced to 12 years in jail for beating a homeless man to death in 2001 – celebrating their imminent parole. Inside their cells, with music and drinks, they filmed the revelry on a cellphone. Prisoners are not allowed either alcohol or phones, and based on the video, the two were taken back to jail and will only be eligible for parole after serving a further 12 months.

These were reportedly not the only perks the Waterkloof inmates had enjoyed. The general opinion was that the prisoners' well-to-do families had sponsored their comfortable prison lifestyles, and that officials had turned a blind eye – meaning that both sides had willingly engaged in corruption.

This begs the question: if the video had not gone viral, would any action have been taken against the offenders? The very officials responsible for security and for looking after inmates are showing that they are vulnerable to corruption – and the nature of their job means that their trustworthiness should be beyond question.

The other side of this coin is that corrupt officials allegedly take food meant for the prisoners, who then have to offer bribes to get the food that is rightfully theirs. A Corruption Watch reporter has drawn attention to this: "The members of the correctional services are stealing food meant for prisoners. Prisoners are receiving very little food. They are starving," our reporter writes.

In his 2014 budget speech, delivered in July, Justice Minister Michael Masutha did not draw attention to any plans to tackle these issues.

We contacted the DCS for comment and clarification of the measures being taken to root out corruption and corrupt officials, but at the time of publishing had not yet received a response. Once we receive it we will update this article accordingly.

Recommendations to tackle corruption and maladministration

The Wits Justice Project (WJP) says that corruption is a co-dependent relationship, where "everyone needs everyone else to be corrupt". The project's co-ordinator, Nooshin Erfani-Ghadimi, speaking to Corruption Watch, notes: "Correctional services corruption is systemic and endemic, and there is impunity because no-one is charged. The system is well entrenched and runs smoothly, and the rate of prosecution is small."

In 2006, the Jali Commission of Inquiry, set up to probe alleged corruption, maladministration, violence and intimidation in prisons, released its 3 500-page final report after an investigation that took five years. It heard the testimony of 516 witnesses over a period of 105 weeks of hearings.

Named for its chairperson, former High Court Judge Thabane Jali, the commission revealed worrying levels of mismanagement and irregularities in South African prisons. It stated that "corruption and maladministration were so rife in most of the management areas investigated as to warrant describing this as part of the institutional culture". It also noted that, while there were some employees in the DCS who were "predominantly driven by the greed and the need to make easy money", there were others who were law-abiding and who sought to comply with rules and regulations.

Officials abusing their power

The commission described other problems, such as the careless disregard of rules pertaining to security, searching of visitors, visitation rights, and use of state assets, among other aspects, that were "done with impunity in that there was little evidence of disciplinary action being taken against the transgressors".

Erfani-Ghadimi also mentions incidents of abuse of power that fall within the interest of WJP, such as officials demanding "toll fees" from families before allowing them to see their relatives, warders selling juvenile prisoners for rape, and neglect of ill prisoners. "Mobile phones are not our worry," she says. "I think it would help them keep in touch with their families. What concerns us are the corrupt acts that affect the human rights of inmates."

A lack of oversight is allowing corruption to reach these worrying levels, she says. "The Judicial Inspectorate [of Correctional Services] is ineffective, but in any case to tackle the problem we need a range of strategies, including the establishment of an independent oversight body with independent prosecutorial powers, and a transparent, open look at the training of officials."

She also suggests praise of those officials who do their job well. "We must reward excellence and pride in the work, while recognising that warders and police are in difficult situations."

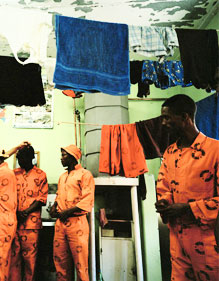

Gangs powerful in prisons

The Jali report did concede that many problems faced by the DCS stemmed from the way it was structured and run before 1994, and in the way its operations had been demilitarised in 1996 without a replacement system being instituted. The resulting loss of leadership had allowed the police union, Popcru, to advance its own leaders and become powerful within the department, and in the late 1990s and early 2000s there was disorder, chaos and slack security – gangs had capitalised on this weakness and there were more escapes than ever before.

"Popcru was essentially the architect of the department's downfall at that time," says lawyer and sociologist Prof Lukas Muntingh, co-founder of the Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative, which operates out of the University of the Western Cape's community law centre.

The Jali report pointed out that gangs were a serious problem – in fact, it noted, there was a suggestion that gangs were actually running some prisons. The absence of corrupt officials would make it easier to tackle the gang problem, it added, although the gangs would still operate if there were no officials to help them on the inside.

Former inmate Dudley Lee took the DCS to the Constitutional Court for allowing him, through negligence, to contract tuberculosis while in prison. One of the points agreed on in court by the parties was that it was the gangs in Cape Town's Pollsmoor Prison who decided whether prisoners suspected of being ill would undergo a sputum test, or not.

Sexual violence, overcrowding, abuse of power, treatment of prisoners, and procurement – among other areas – were also sources of concern, noted the Jali report. It made numerous recommendations to tackle mismanagement and inefficiency but, Muntingh explains to Corruption Watch, most of those that were implemented were aimed at a higher level of management, and not at the day-to-day "operational corruption", which continues today.

"They set up the Departmental Investigation Unit and Code Enforcement, and reinstituted the disciplinary code – this is much needed." He describes a search at Westville Prison, in Durban, that unearthed over 1 000 cellphones. "These don't come in with the prisoners alone. The Jali Commission suggested mobile blocking but [DCS] has hesitated to implement this."

He says current conditions are lucrative for officials, so it is against their personal interests to clamp down on corruption.

The Jali Commission also recommended that the department appoint an independent outside agency – a prison ombudsman – to investigate corruption. Although the department already had an anti-corruption unit, it said, it suggested the unit was ineffective in dealing with the problems. The suggestion was rejected by the DCS.

Other Jali recommendations included various improvements to security, three meals a day for prisoners, retaining human rights officials, training staff to deal competently with the implications of sexual violence and to protect victims, the introduction of an internal witness protection system, and better stock control and reconciliation of goods and invoices, among others.