|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), released today by anti-corruption movement Transparency International (TI) reflects the apparent stagnation of South Africa’s anti-corruption efforts. With a score of 41, the same as last year, the country remains stubbornly below the global average of 43, having dropped by three points since 2019.

According to Corruption Watch (CW), TI’s local chapter, which has been tracking progress on the index for the past 13 years, this disconcerting score suggests that there have been few gains or concrete efforts to tackle the large-scale problem of corruption.

The CPI assesses 180 countries and territories around the world according to the levels of public sector corruption perceived by experts and surveys from businesspeople. It draws on 13 independent data sources and scores countries from zero to 100, where zero is highly corrupt and 100 is very clean.

It is worth noting that the CPI measures perceptions of corruption, not corruption reported or experienced by members of the public. For this reason, perceptions may differ from the reality on the ground.

In South Africa, some encouraging developments in attempts to address corruption include the establishment last year of the Investigating Directorate Against Corruption as a permanent entity within the National Prosecuting Authority, along with reports from the Asset Forfeiture Unit and the Special Investigating Unit that over R10-billion has been recovered in state capture-related cases .

Global trends

The 2024 CPI shows strong links between two of humanity’s biggest challenges – the climate crisis and corruption, which undermines climate action by misdirecting resources, enabling harmful practices, and stifling progress. It also highlights the stark contrast between nations with strong, independent institutions and free and fair elections, and those with repressive authoritarian regimes. What it terms full democracies (24 countries) have a CPI average of 73, while flawed democracies (50 countries) average 47 and non-democratic regimes (95 countries) just 33.

While some non-democratic countries might be perceived as managing certain forms of corruption better than more democratic countries, the broader picture shows that democracy and strong institutions are crucial for combating corruption fully and effectively.

Some countries may have authoritarian or draconian anti-corruption measures, while others, even those at the top of the CPI, may enable corruption. The index does not capture how countries can facilitate transnational corruption, via stolen funds laundered through their economies and the bribery of foreign officials. This is where the main weaknesses of high-scoring countries lie.

The fact is that most countries have made little to no progress in tackling public sector corruption in more than a decade, with over two-thirds of countries scoring below 50 out of 100, a strong indication of serious and persistent corruption problems. This could have huge and potentially devastating implications for global climate action.

Corruption and the climate crisis

Corruption is a global problem, affecting every country and obstructing efforts to properly confront climate change. Where corruption thrives, climate initiatives often fail, for several reasons:

- By undermining the development and enforcement of critical climate and environmental policies, corruption obstructs efforts to implement stringent regulations, reduce emissions, and promote clean energy initiatives.

- Undue influence on climate policy occurs in countries with both high and low corruption levels – but in wealthy, developed countries, this interference undermines global progress the most.

- Countries with lower corruption levels generally show better readiness to face the challenges posed by climate change – but many are still not adopting the ambitious measures necessary to tackle the climate crisis, partly because of undue influence by businesses.

- A lack of adequate transparency and accountability mechanisms increases the risk that climate funds may be misused or embezzled.

Accordingly, the CPI makes several recommendations, urging governments, international organisations, and businesses to place corruption at the centre of the global debate, and to focus on four key actions:

- to put integrity at the centre of climate efforts, prioritising the integration of robust anti-corruption measures into climate finance, policies, and projects to achieve real impact.

- to shield climate policymaking from undue influence at national, regional, and international levels.

- to enhance investigations, sanctions, and protections to combat corruption, which will deter environmental crimes and reduce impunity, and

- to strengthen citizen engagement in climate investments, enabling those affected by the climate crisis to help tailor the solutions.

South Africa’s hosting of the G20 Leaders’ Summit this year provides a vital opportunity to advocate for G20 countries to make increased climate finance commitments that do not merge debt repayments, private financing and loans as a substitute for direct mechanisms to mitigate the climate crisis.

CPI scores, changes, between 2012-2024

Between 2012 and 2024, 32 countries improved, 47 countries declined, and 101 countries stayed the same. Interestingly, the countries with the most upward movement include Bahrain, Cǒte d’Ivoire, Moldova, Dominican Republic, Bhutan, and Estonia. Conversely, those with the sharpest downward trajectory over this period include El Salvador, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Russia, Austria, and eSwatini.

For the seventh year in a row, Denmark tops the list with a score of 90, followed by Finland and Singapore with scores of 88 and 84 respectively. At 83, New Zealand drops out of the top three for the first time since 2012, but remains in the top 10, together with Luxembourg (81), Norway (81), Switzerland (81), Sweden (80), the Netherlands (78), Australia (77), Iceland (77), and Ireland (77).

Meanwhile, countries experiencing conflict or with highly restricted freedoms and weak democratic institutions occupy the bottom of the index. South Sudan (8), Somalia (9), and Venezuela (10) take the last three spots. Syria (12), Equatorial Guinea (13), Eritrea (13), Libya (13), Yemen (13), Nicaragua (14), Sudan (15) and North Korea (15) complete the list of lowest scorers.

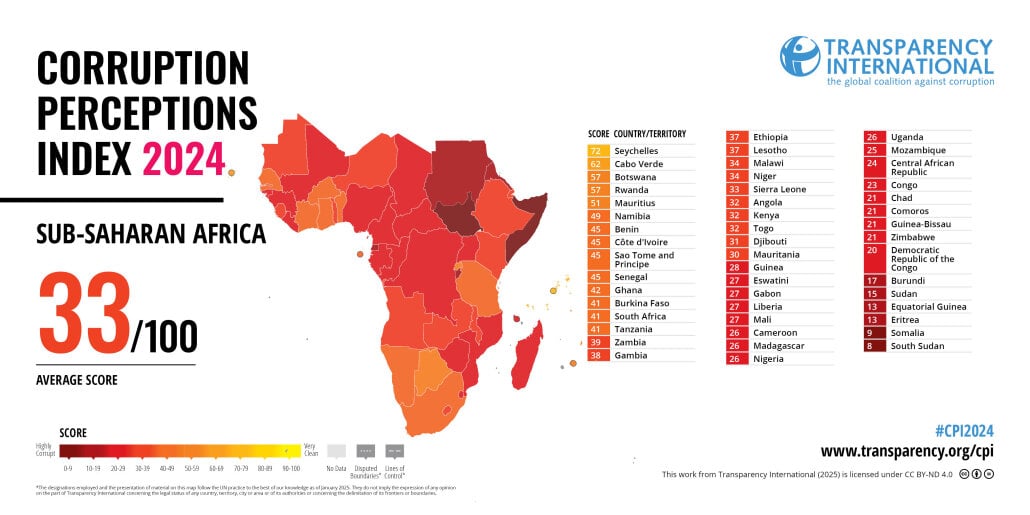

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is still the lowest performing region, with an average score of 33 out of 100, and with 90% of countries scoring below 50. And yet there were African countries that invested in anti-corruption and made remarkable progress.

The highest scorers in the region were Seychelles (72), Cabo Verde (62), and Botswana and Rwanda both at 57. The lowest scorers – Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Somalia, and South Sudan – declined further this year.

For media enquiries contact:

Oteng Makgotlwe

Cell: 076 473 8336 E-mail: OtengM@corruptionwatch.org.za