By Janine Erasmus

Every day organisations operating in new and emerging markets face the risk of getting involved in corruption – either they feel they should commit it to get ahead, or they try to avoid it and fear that they’ll be left behind. But is there a way to get ahead in business without being corrupt? According to experts in the risk sector, yes there is.

While emerging markets have lagged in taking a tough stance against corruption, it seems that they are at last coming to the party – according to the International Business Attitudes to Corruption Survey 2014/2015 carried out by global risk consultancy Control Risks. The survey named this heightened awareness in emerging markets as one of three powerful drivers that are “sharpening international corporate attitudes to corruption”. Control Risks polled 638 companies that operate all over the world, and singled out China, India and Brazil as developing countries that are tightening their anti-corruption laws.

In our new longer-running series, Corruption Watch takes a look at the reality of corruption and examines attitudes and practises elsewhere on the African continent. We start with Nigeria.

In March in a live webcast from Lagos, a panel of experts shared their views and experiences of dealing with corruption in Africa’s business environment, with a focus on the West African country that has had its fair share of bad press relating to corruption.

The panel included Richard Fenning, CEO of Control Risks; Tom Griffin, Control Risks’ MD for West Africa; and Uche Orji, CEO of the Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority and formerly with Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Arthur Andersen.

The three panellists expressed positive views of the changing African stance towards corruption, and agreed that besides legislation and regulations, civil society and social media are playing their part in driving the change.

“Certainly in the last 18 months in Nigeria we’ve seen a sea change in terms of the accountability of government to not embark on corrupt practices,” said Griffin. “A lot of that is driven by social media: Twitter, Facebook, etc. Individuals are expecting more of the government.”

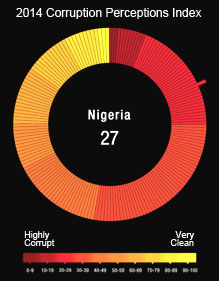

Nigeria’s ranking of 136 – out of 175 countries surveyed – on the 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), published by Transparency International, bears out this statement. This position was its best in four years – in 2013 the country ranked 144, in 2012 it was 139 and in 2011 it was 143. The country’s score also improved slightly over 2013, from 25 to 27.

In contrast, on the 2000 CPI Nigeria was fingered as the most corrupt country in the world.

However, TI’s 2013 Global Corruption Barometer showed that 72% of Nigerians felt corruption has increased significantly. And in TI’s 2013 Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index, which rated 82 countries on their defence-related corruption risks and vulnerabilities, Nigeria’s score indicated a very high level of corruption risk.

Greater awareness of corruption and its consequences

Griffin said that in his experience in the region, there is a greater awareness, especially in the boardroom, around legislation such as the US’s Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) or the UK Bribery Act. “Organisations realise that they need to change their operating models in order to successfully work in places like Nigeria.”

But Nigeria still suffers from what Fenning termed as “perception problems”, although he conceded that the tide may be turning in that respect.

“We are broadcasting at a time when Nigeria is gripped with controversy over the [recently concluded] election process, and there is so much in the news about … Boko Haram. But we want to put those issues aside and look at areas where Nigeria is changing. One of those key areas is its attitude towards corruption and compliance.”

Orji agreed, saying that assumptions about the business environment in the Western world and in Africa are very different – and not entirely accurate. “There is an assumption that systems or controls work very well in countries like the US; data verification is easy, and there’s a certain level of competence assumed of the staff who are charged with implementing this compliance regime. In Nigeria, the assumptions were exactly the opposite when I started my career – you can’t verify data, control systems don’t work, and compliance systems do not have competent staff to run them.”

This might have been the situation many years ago, he said, but despite substantial changes – data can now easily be verified in Nigeria, and it’s easier to implement effective control systems – the assumptions continue to persist. “I think it’s an element of perception that is historical but that continues to influence the way people approach business in Africa.”

Other factors driving the behavioural change towards corruption, said Orji, are easier access to information such as audit and forensic reports, and people’s ability to communicate more effectively through channels such as social media.

He mentioned the FCPA, saying: “Now you could be jailed in the US for actions that commenced in Africa – that never used to happen. So if you’re a multinational coming from the US to do business in Nigeria, you realise that you couldn’t get away with things you could get away with 10, 15 years ago.”

That change in attitude influences the tendency of governments to ask for favours from multinationals, said Orji. “I don’t think this will change overnight, but … people are asking for accountability. People are looking at your lifestyle, asking questions about it, which we didn’t do a decade ago, and I think that is influencing the way officials behave in general.”

Private companies too are realising that if they operate in an ethical and proper manner, they have a distinct competitive advantage, said Griffin, as a clean track record facilitates institutional investment or the establishment of relationships and joint venture partnerships with major international organisations.

Fenning summed up by saying that pressure for change is coming from international regulation, a groundswell in change of public perceptions and opinion, which has “an irrevocable momentum about it”, and the realisation that the ethical, compliant, anti-corrupt way of doing business is ultimately good business.

Technology a driver of anti-corruption

Technology is helping the Nigerian government to eliminate corruption in its ranks. The processing system for salaries has improved to the extent that ghost workers are hardly seen any more. In the agriculture sector the fertiliser distribution system was an avenue for corruption, but new systems are changing that. The pension system has also been revamped – “I knew people who wouldn’t get a dime of their pensions after making years and years of contributions,” said Orji, “but that’s been reformed. A lot of what it takes to fix corruption is institutional, and it’s those institutions, one by one, that will build the irrevocable momentum, as you call it.”

The move to a cashless society was another boost for anti-corruption, said Fenning, with countries like Nigeria and Kenya spearheading this move.

“The implementation has only just started in the last 12 months, but I think that over time it will make it easier for people to not succumb to the temptation of corruption,” agreed Orji. “If there’s a record to be kept of the transfer you won’t want it pointing at you.”

The webcast wrapped up with a discussion on whether it was possible to do away with facilitation payments, which are a specific form of bribery. International regulations differ on their treatment of such payments, said Fenning, and despite all the talk and the legislation and policies, some international companies can’t seem to get away from this problem.

“A recent Control Risks anti-corruption survey indicated that 20% of respondents were asked for a facilitation payment as a potential way to smooth business transactions,” said Griffin. “However, it’s vital that organisations set an expectation up front, with a potential partner or investor, that this is not the way they will do business. And they must set that tone not just at the highest level but in the middle management team too. Also, they should be comfortable walking away from business if there is any doubt of the deal making it past the ethics or compliance committees of the company.”

Corruption takes two, he said – there is a demand and a supply. But organisations that are less willing to give money up front actually benefit in the long run.

However, none of this will make a difference if leadership, systems and controls, and anti-corruption messaging across the organisation are inadequate, Orji warned. “If your environment is poorly designed, people will take advantage of it – this doesn’t only apply to Nigeria.”