|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

More than 300 informal settlers in Sol Plaatje squatter camp near Roodepoort are still waiting for RDP houses they were promised in 1999. Although most of the houses have been built, many have been made uninhabitable by vandalism and illegal occupation.

More than 300 informal settlers in Sol Plaatje squatter camp near Roodepoort are still waiting for RDP houses they were promised in 1999. Although most of the houses have been built, many have been made uninhabitable by vandalism and illegal occupation.

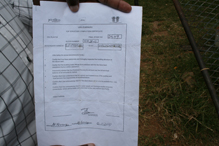

Despite this, officials from the regional housing department have persuaded the “owners” to sign documents, also referred to as “happy letters”, confirming that they are satisfied with their houses. The residents say they signed the documents because they thought they were the title deeds to their homes.

Corruption Watch has copies of the documents.

Of the 2 558 units that have been built in Sol Plaatje, 2 200 were allocated to the rightful owners, but the remainder have been invaded or vandalised due to a lack of security. As a result, the residents who should rightfully be occupying them continue to live in cramped conditions in shacks and flats.

According to Sol Plaatje housing development community liaison officer Joseph Letjoko, some of the houses were invaded because they were left empty for a long time without being allocated, while others have no toilets, pipes, windows or doors due to vandalism.

According to Sol Plaatje housing development community liaison officer Joseph Letjoko, some of the houses were invaded because they were left empty for a long time without being allocated, while others have no toilets, pipes, windows or doors due to vandalism.

Fearing that if they wait for too long their vandalised houses will be further damaged and believing promises from the contractor that the existing damage will be repaired, some of the rightful owners have moved into the damaged homes, said Letjoko.

R104-million was allocated for the housing development, but, said Letjoko, “it look like they used R20 000. If you look at where our subsidies have gone you can’t see that much difference.” The houses are so shoddily built that many were flooded during the rainy season, he said.

Corruption Watch has a copy of the budget plans and has photographs showing the substandard work.

According to Letjoko, each successful housing applicant received a subsidy worth R40 000, which was ploughed into the development. The overall budget also included a R100 000 allocation for a playground and R75 000 for greening, both of which the community has yet to see, he said.

According to Letjoko, each successful housing applicant received a subsidy worth R40 000, which was ploughed into the development. The overall budget also included a R100 000 allocation for a playground and R75 000 for greening, both of which the community has yet to see, he said.

Residents also complain that stands have not been demarcated and fenced and roads have yet to be built, despite these being promised features of the development.

Relocation

Located south of Roodeport around an abandoned mine hostel, Sol Plaatje was established in 1999 as a settlement for people who were evicted from three other informal settlements – Maraisburg, in 1999; Woerus, in the Honeydew area, in 2000; and Mandelaville, near Diepkloof, in 2001.

At the time the City of Johannesburg, which was responsible for the relocation, undertook to have houses built, but eventually residents were forced to go to court to compel the city to honour its undertaking. Not until the court’s decision, ordering the city to provide all applicants with formal housing within two years, was handed down in 2004 were any steps taken to provide housing.

At the time the City of Johannesburg, which was responsible for the relocation, undertook to have houses built, but eventually residents were forced to go to court to compel the city to honour its undertaking. Not until the court’s decision, ordering the city to provide all applicants with formal housing within two years, was handed down in 2004 were any steps taken to provide housing.

The Johannesburg Social Housing Company (Joshco), given the task of developing the Sol Plaatje settlement, contracted Motheo Construction Group to refurbish the existing single-storey mining hostels and turn them into double-storey blocks of flats, to build RDP units and new flats and to lay water and sewage pipes.

In a press statement issued in August 2007, Joshco stated that “the entire redevelopment is expected to be completed in 2009”. Among the facilities Joshco was supposed to provide was street lighting and the company was also supposed to facilitate the township’s connection to the electricity grid. Now, in 2012, residents still do not have access to electricity.

Although a clinic has been built it cannot be opened because of the absence of electricity and the community has been given no indication of when power might be supplied, said Letjoko. “We haven’t been informed of anything,” he complained. “We are in the dark; we don’t know when we’ll get electricity.”

Although a clinic has been built it cannot be opened because of the absence of electricity and the community has been given no indication of when power might be supplied, said Letjoko. “We haven’t been informed of anything,” he complained. “We are in the dark; we don’t know when we’ll get electricity.”

According to Tim Potter, the director of Motheo Construction, electricity is not the only element that is missing – the settlement has no roads or storm-water drains. “Normally we would have been asked to do that process, but there was no funding,” said Potter. Construction in the area began in February 2007 and was completed in July 2009, he said.

According to Potter, houses were approved for 2 200 people and 300 applications were rejected. “You can only give occupation to the people who have been approved for a subsidy. And there are lots of reasons why you cannot be approved … if you are not a South African citizen, you don’t have a dependent or you’ve already had a subsidy and have a house somewhere else.”

However, the City of Johannesburg and the Department of Human Settlements were working on putting those who had not been provided for through the system to enable them to get houses, he said.

However, the City of Johannesburg and the Department of Human Settlements were working on putting those who had not been provided for through the system to enable them to get houses, he said.

Letjoko refuted this, saying only 15 applications had been rejected permanently and about 300 residents whose houses had been vandalised or invaded had already signed for them, which meant their subsidies had been approved. “You can’t sign for a house without being approved,” he said.

While Potter claimed Motheo has repaired 180 vandalised houses, Letjoko says only about 30 have been repaired so far.

“We sat with Joshco and then measured what had been stolen,” said Potter. “We said we would repair the vandalised houses and only ask for payment for material and labour.”

He added that houses were vandalised during and after construction and it had been difficult to get the community to self-police.

Letjoko, however, asserted that the community should not have been expected to self-police because an amount to the tune of R289 000 had been set aside for security.

Furthermore, the municipality should have acted on an order issued by the court in 2010 to evict the invaders. Instead, the mayoral committee had halted the process during the 2011 local elections, saying they could not evict people during elections, he said.

Referring to the renovated hostels, Letjoko told Corruption Watch that the contractor “just patched some houses, extended concrete slab houses with bricks and re-used old roofs”.

The two-room flats that were built do not meet the Gauteng department’s housing norms and specifications for low-cost housing for 2008/9, which stipulate that each unit must have two bedrooms.

The internal walls of the RDP houses have not been plastered or bag-washed and the internal walls of the renovated hostels have not been repainted. Potter said these deficiencies were due to financial restraints and that no paint had been specified for the walls, with the exception of the bathrooms, for waterproofing purposes. The specifications had been developed in conjunction with Joshco and the council and were a function of a limited budget.

According to the Housing Act of 1997, explained Potter, each South African is eligible to a certain amount as a housing subsidy. The amount was a combination of a fixed budget provided by the Department of Human Settlements and municipal grant funding. “Joshco had been allocated a certain amount and we were required to work within that budget,” he said.

“[The flats] were originally prefabricated concrete hostel dwellings and so the design of the new units was restrained by the original structure. This is the reason why two bedrooms were not designed. The free-standing units do have two bedrooms.”

Re-used roofs simply needed to be replaced if roof tiles came off, said Potter.

Another complaint from Sol Plaatje residents was that they had not yet received their title deeds and, said Letjoko, the informal settlement has not yet been declared a township.

Potter says the reason for residents not receiving title deeds was that the land transformation process is still ongoing.

“Often these land processes can take years,” he explained. “The land was owned by private individuals. Joshco had to then arrange for the gathering of those individual purchases and get their commitment in terms of deed of sales to actually combine ownership under the City of Johannesburg.”

He said a township registry will be opened this month and once the general town plan is approved individual title deeds will be registered. But this, said Potter, will depend on whether the council receives the necessary funding.

Back to court

Letjoko said this information had not been communicated either to him or to members of the community and he had approached the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (Seri) to help him with the matter.

“We will meet them in court,” he said.

Seri attorney Osmond Mngomezulu confirmed that he had received the documents from Letjoko concerning the Sol Plaatje housing development but that nothing had yet been done because Seri was inundated with cases. However, Seri plans to hold a meeting with the Sol Plaatje community on Sunday May 19 to investigate the matter further.

“This matter is not a straightforward one, it’s complex and requires attention,” said Mngomezulu.

The victims

Sibongiseni Ngcobo, 43, whose house has been invaded, has made repeated attempts to regain it, to no avail. Shortly after he signed the “happy letter” he had prepared to move into his new home, only to find that someone had already occupied it.

After a squabble with the invader during which he ended up breaking the door, the Roodeport police arrested him.

“I showed them the papers I had signed which [proved] I was the rightful owner and they still arrested me,” said Ngcobo. “Here the rightful owner is arrested and not the person who has invaded their house.”

He is now forced to live with his wife and four children in a two-room flat belonging to a relative.

Another resident, Gogo Makgosimang Matsuwoni, 71, signed a letter of satisfaction in July 2010, but still lives in a one-room shack while another person has taken over her house.

“I can’t apply for a house and then someone else gets it,” said Matsuwoni. “Is that right? [But] when it’s time for elections we’re all told to vote.”

No response

When Corruption Watch approached the City of Johannesburg to respond to the complaints of the Sol Plaatjie residents, housing communications representative Bubu Xuba referred us to Joshco, saying it was responsible for the project.

Corruption Watch put forward a set of questions to Joshco, asking why the eviction process had been halted; what had happened to the money set aside for security, greening and a playground; why there were still no roads and electricity and when the residents would receive their title deeds.

Despite giving Joshco two weeks to respond, Corruption Watch has yet to receive a reply.