The 2018 Financial Secrecy Index (FSI), an initiative of the Tax Justice Network (TJN), was launched recently. The FSI ranks jurisdictions according to their secrecy and the scale of their offshore financial activities. It shies away from being political, positioning itself instead as a tool for understanding global financial secrecy, tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions, and illicit financial flows or capital flight.

The purpose of the index is to help identify and expose the most important providers of international financial secrecy and in doing so, it reveals that traditional stereotypes of tax havens are not entirely accurate. The world’s most important providers of financial secrecy harbouring looted assets are mostly not small, palm-fringed islands as many suppose, says TJN, but rather, they’re some of the world’s biggest and wealthiest countries.

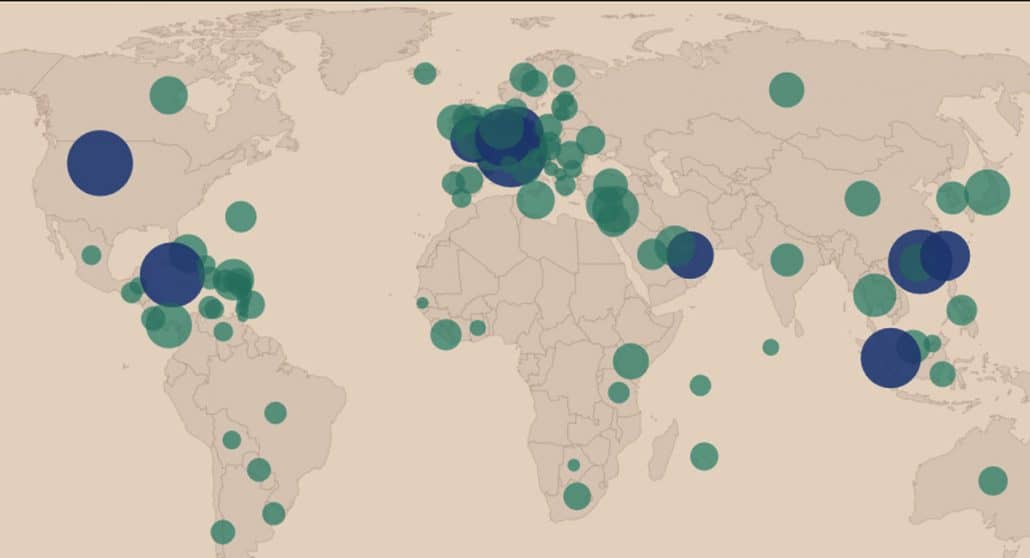

Rich OECD member countries and their satellites are the main recipients of or conduits for these illicit flows, the FSI reveals. This year’s index focuses on 112 jurisdictions, including the likes of China, Japan, Germany and France, which are traditionally considered to be tax havens.

Crunching the numbers

There are two components to the FSI – a qualitative and a quantitative rating, The qualitative measure looks at a jurisdiction’s laws and regulations, international treaties, and more, to assess how secretive it is. It then gets assigned a secrecy score between 0 and 100: the higher the score, the more secretive the jurisdiction.

The quantitative measurement attaches a weighting to take account of the jurisdiction’s size and overall importance the global market for offshore financial services.

An FSI value is then arrived at, using a special formula – the cube of a jurisdiction’s secrecy score multiplied by the cube root of its global scale weight. This final score is used for the ranking, as a measure of each jurisdiction’s contribution to the global problem of financial secrecy.

The FSI share of a jurisdiction (the “secrecy actually provided in the world”) is calculated as a portion of the sum of all the FSI values of all 112 jurisdictions = 31 710 65. This is taken as 100%, and each jurisdiction is assigned a percentage.

South Africa ranked 50 out of 112, recording an FSI value of 216.43, and its secrecy score is 56, showing that the country is leaning towards the ‘moderately secretive’ ranking of 31-40.

A secrecy score approaching 100 means that a country is exceptionally opaque – this grouping included Antigua and Barbuda, and Vanuatu, as well as the Bahamas, the UAE, and Brunei. Lack of transparency and unwillingness to engage in effective information exchange make secrecy jurisdictions such as these more attractive locations for routing illicit financial flows and for concealing criminal and corrupt activities.

The UK scored the best, in terms of secrecy score, followed by Slovenia and Belgium. South Africa’s secrecy score of 56 was matched by Austria and New Zealand, while its global weighting of 0.18% was dwarfed by the 22.3% of the US, followed by the UK’s 17.4% and Luxembourg’s 12.5%. No other country scored double digits on the quantitative (weighting) side.

In terms of overall secrecy – qualitative and quantitative scores combined – the worst countries were, unsurprisingly, Switzerland, followed by the US, Cayman Islands, Hong Kong, Singapore and Luxembourg. In fact, the FSI says, Switzerland’s FSI value and FSI share (secrecy actually provided) is 96 times larger than that of Montserrat, with the lowest FSI value and FSI share.

Operating in secrecy

“Secrecy jurisdictions set up laws and systems which provide legal and financial secrecy to others, elsewhere,” the FSI notes.

Secrecy scores are calculated as the average of a country’s performance in 20 indicators, including banking secrecy, recorded company ownership, public company ownership, anti-money laundering, country-by-country reporting, and more. The 20 indicators are divided into four broader categories, namely ownership registration, legal entity transparency, integrity of tax and financial regulation, and international standards and co-operation.

South Africa fared the worst in category two, legal entity transparency, and its best result was for category three, integrity of tax and financial regulation.

The country’s secrecy score of 56.10 is the lowest of the nine African jurisdictions included in the FSI 2018, the report reveals – yet its global significance is the greatest of any of the African countries. The other African countries were Liberia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mauritius, Seychelles, Ghana, Botswana and Gambia.

And while South Africa is the least secretive of the African countries analysed, a problem persists because secrecy undermines South Africa’s own tax base, the FSI points out. The country’s elite, as well as domestic and foreign multinational companies operating inside its borders exploit weaknesses in legislation and use other secrecy jurisdictions to reduce their tax obligations in a country with deep inequality.

The entanglement of business and state interests and the use of secrecy jurisdictions dates to apartheid-era sanctions busting in which many countries were complicit. But, the FSI reminds us, this ensnaring of the state by business interests did not stop with the end of the apartheid regime. In fact, the Gupta Leaks of almost a year ago reveal the extent of what has infamously become known as state capture.

For a highly detailed look at the FSI analysis of South Africa, click here.

All is not lost

The research work done for the FSI reveals that there are improvements in the global situation. “The worldwide financial crisis and ensuing economic crisis, combined with recent activism and exposure of these problems by civil society actors and the media, and rising concerns about inequality in many countries, have created a set of political conditions unparalleled in history.”

As a result, the world’s politicians have been forced to take notice of tax havens and, notes the FSI, “for the first time since we first created our index in 2009, we can say that something of a sea change is underway.”

Around the world, the topic of financial secrecy is on the lips of many, and leaders are putting new measures into place to tackle the problem. Still, there can be no complacency or let-up of pressure. “The edifice of global financial secrecy has been weakened – but it remains fully alive and hugely destructive. Despite what you may have read in the media, Swiss banking secrecy is far from dead,” the FSI cautions, adding that people around the world must continue to apply pressure, or the momentum could be lost.

One of the ways in which the problem must be tackled is to identify as accurately as possible the jurisdictions that make it their business to provide offshore secrecy, says the FSI. And that is what the index is aiming for.