By Kwazi Dlamini

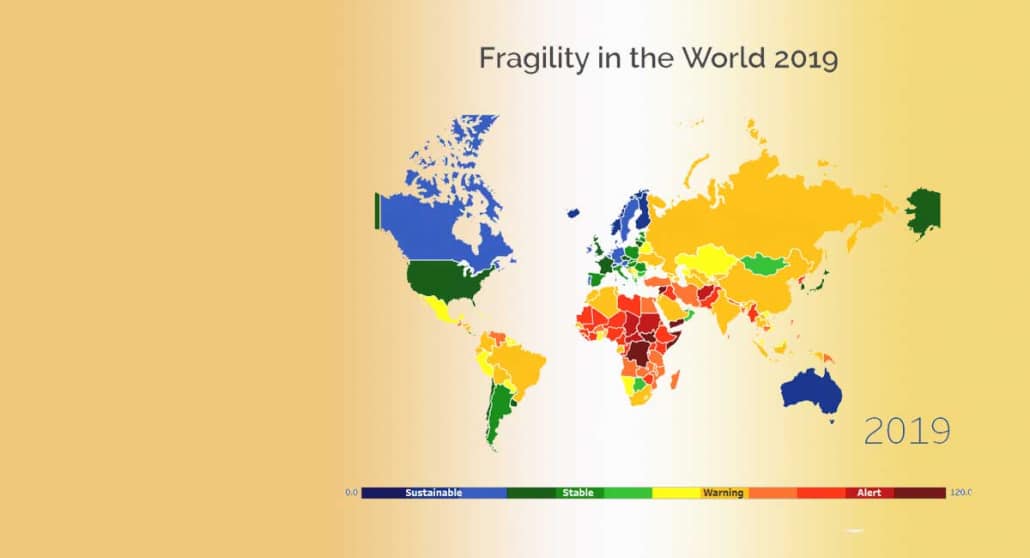

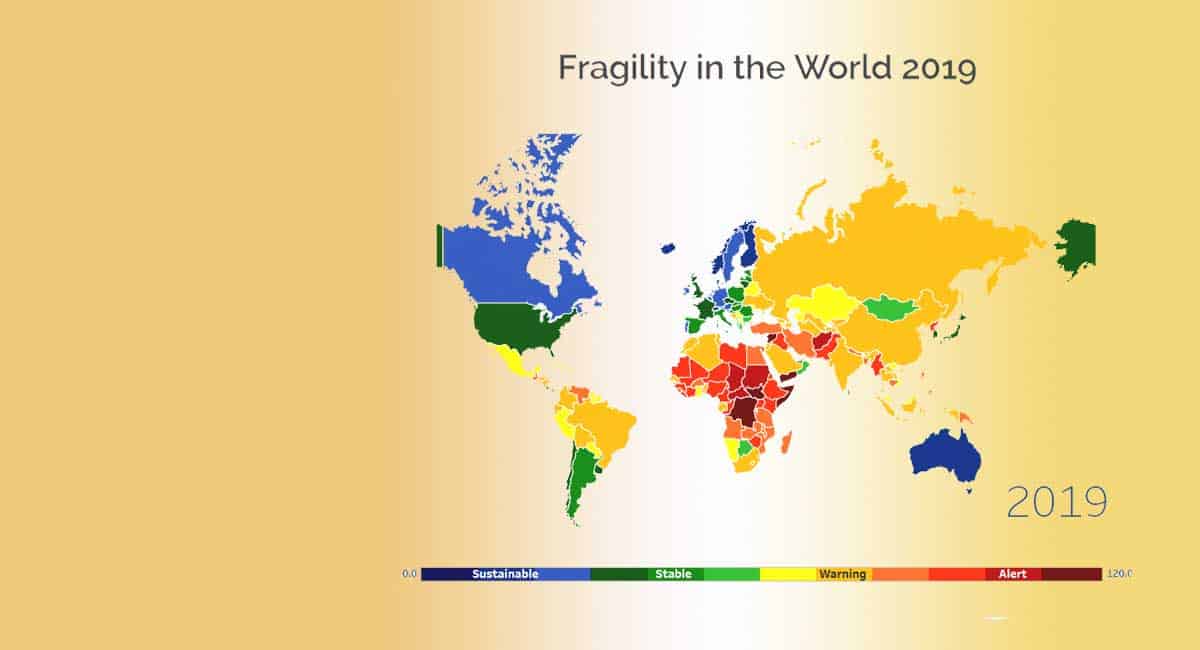

The 2019 Fragile States Index (FSI), researched and released by Fund for Peace, indicates those countries that are fragile, on the brink of collapse, or are vulnerable to collapse. Using 12 indicators, the index rates countries on a scale of 0 to 10 for each indicator, with 0 being the most stable while 10 indicates the least stable.

The FSI’s main purpose is to assess the vulnerability of states and has been released annually since 2005, making this the 15th edition. It includes 178 countries who are members of the UN and on which there is enough data to correlate with the FSI indicators.

The 12 indicators fall into four broad categories – Cohesion, Economic, Political, and Social. They are:

1. Security Apparatus – considers the security threats to a state, and also takes into account serious criminal factors, such as organised crime and homicides, and perceived trust of citizens in domestic security.

2. Factionalised Elites – considers the fragmentation of state institutions along ethnic, class, clan, racial or religious lines, and also factors in the use of nationalistic political rhetoric by ruling elites, often in terms of nationalism, xenophobia, etc.

3. Group Grievance – focuses on divisions and schisms between different groups in society, particularly divisions based on social or political characteristics, and their role in access to services or resources, and inclusion in the political process.

4. Economic Decline and Property – considers factors related to economic decline within a country, and also takes into account sudden drops in commodity prices, trade revenue, or foreign investment, and any collapse or devaluation of the national currency.

5. Uneven Economic Development – considers inequality within the economy, irrespective of the actual performance of an economy.

6. Human Flight and Brain Drain – considers the economic impact of human displacement (for economic or political reasons) and the consequences this may have on a country’s development.

7. State Legitimacy – considers the representativeness and openness of government and its relationship with its citizenry, as well as the population’s level of confidence in state institutions and processes, and the effects where that confidence is absent, manifested through mass public demonstrations or sustained civil disobedience.

8. Public Services – refers to the presence of basic state functions that serve the people, such as health, education, water and sanitation, transport infrastructure, electricity and power, and internet and connectivity. It may include the state’s ability to protect its citizens through perceived effective policing.

9. Human Rights and Rule of Law – considers the relationship between the state and its population insofar as fundamental human rights are protected and freedoms are observed and respected.

10. Demographic Pressures – considers pressures upon the state deriving from the population itself or the environment around it.

11. Refugees and Intentionally Displaced Persons (IDPs) – measures the pressure upon states caused by the forced displacement of large communities as a result of social, political, environmental or other causes, measuring displacement within countries, as well as refugee flows into others.

12. External Interventions – considers the influence and impact of external actors in the functioning – particularly security and economic – of a state. This indicator cuts across all the others.

With all these indicators taken into consideration, South Africa scored 71.1 out of a possible 120. This puts the country into 88th place on the list, from 85th in 2018. However, this still means it is a fragile state.

The most improved country this year is Ethiopia, and the least improved is Venezuela, along with Brazil. The most fragile country in the world, according to the FSI, is Yemen. In the history of the FSI, the report notes, only three other countries have held the top spot, and all are from Africa – Cote d’Ivoire for the first year, and then Somalia and South Sudan for the rest of the time.

In 2019, an African nation ranked for the first time ever in the Very Stable category – Mauritius has become the first country on the continent to achieve this. Meanwhile, Singapore became the first Asian nation to move into the Sustainable category, which is almost the best possible situation, topped only by Very Sustainable.

Warning for South Africa

South Africa’s mediocre score puts it into the Warning band, where the scores are between 70 and 90, and this is no surprise. Since achieving its best score of 55.7 in 2006, the country’s overall trend over the last 13 years is one of worsening stability. In only four of those years – including 2019 – has the trend been positive. An analysis of the shifts over past decade reveal that South Africa is the 13th most worsened country (just behind the US in 12th place).

The only African country that made it into the top 20 of most improved countries over the past decade countries is Zimbabwe.

Most of Africa falls into the lower half of the index. Only Mauritius (38.9), Seychelles (55.2) and Botswana (59.5) achieved a respectable rating on the FSI 2019.

For many years, the report states, there has been a wide perception of a strong association between African nations and fragility. This perception is not unfounded — in the 2019 FSI, 21 of the 30 most fragile countries are to be found on the African continent. But Mauritius is a clear example that Africa is also home to some of the world’s more stable countries — in 2019 it scored within less than one point of the US, while Seychelles and Botswana are also ranked as Stable.

South Africa has fared particularly badly in terms of cohesion, with its worst showing in the Security Apparatus indicator. Factionalised Elites also worsened while Group Grievance continued to improve.

In terms of economic indicators, the average has remained fairly stable although the individual indicators have shown movement, especially Economic Decline, while Uneven Economic Development has improved.

For political trends, South Africa worsened most in terms of State Legitimacy, while Human Rights remained fairly stable and Public Services went up and down. For social indicators, there was a marked improvement in both Demographic Pressures and Refugees and IDPs, from highs in the early part of the decade.

A country of ups and downs

South Africa was named the most unequal country in the world earlier this year by the World Bank in terms of economic development. The country also fell into recession in late 2018, while the issue of inequality has been attributed to lack of service delivery to the marginalised.

Violation of human rights is not as common in South Africa as it is in other countries on the continent, but it is not entirely immune to such violations. Issues such as police brutality continue to make the news, while lack of service delivery as a human rights violation is a highly debatable topic – the South African Human Rights Commission states that: “healthcare, food, water, and social security – account for the third highest human rights violations”.

South Africa has one of the most independent judiciaries on the continent but is still prone to inadequate and uneven application of the rule of law – people who are in higher or respected positions in society and those who have money are expected to get off lightly for their crimes.

Another indicator well known to South Africa is that of refugees and illegal immigration. Over 2.2-million immigrants are in South Africa and close to a million of those are illegal immigrants. These staggering numbers have led to a backlog of applications for those seeking asylum which eventually leads to illegal immigration and victimisation of those not born in the country. In addition, those who apply for refugee status often fall victim to corruption, with unreasonable delays in getting their papers, meaning that they are undocumented through no fault of their own.

Growing political tensions and social division may do South Africa further damage in future FSIs – however, the election of Cyril Ramaphosa as president of the country may revive some faith among citizens. Ramaphosa has promised to get rid of corruption and improve the lives of the people through service delivery. After his party, the ANC, won the most recent elections he made strides on some of those promises by excluding from his cabinet certain individuals who have been implicated in corruption. Ramaphosa also cut the number of cabinet members to reduce costs, and slashed the budget for his inauguration.

This will to curb unnecessary spending of public funds seems to have invoked similar feelings to other political leaders. Dr Zamani Saul, newly elected Northern Cape premier, has promised to cut off unnecessary spending in the province- one of the poorest in South Africa. Saul said that instead of luxury vehicles and blue lights escorts for government officials, all these funds will be used to purchase new ambulances. Providing new ambulances will improve the health care system and that also includes some of the FSI indicators.

Ramaphosa’s and Saul’s stances on curbing unnecessary spending was widely applauded, with people calling for more leaders to follow suit.