They are vaunted for being “brave truth tellers”, widely admired and praised for criticising graft and corruption in the ruling ANC.

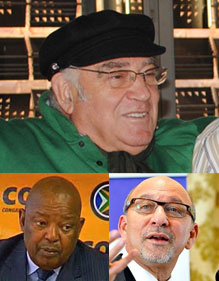

But that is only one side of Trevor Manuel, Ronnie Kasrils and Mosiuoa Lekota. For the former Cabinet ministers are also responsible for approving, stridently defending or championing the controversial, corruption-ridden R71-billion purchase of arms in 1999.

Which is why the three have been ordered to appear before the Arms Procurement Commission, and while their testimony is eagerly awaited, their appearance will also be the height of irony.

This is especially true in the case of former finance and outgoing minister in the Presidency Trevor Manuel, who is scheduled to testify shortly.

For it is widely accepted that Manuel – under whose watch the original R30-billion deal was signed and who was a member of the Cabinet sub-committee tasked with overseeing the deal – was opposed to the deal.

“There was considerable debate in Cabinet about the wisdom of the arms deal. Indications are that the financial cluster, and particularly finance minister Trevor Manuel … (was) fiercely resisting the deal,” Paul Holden and Hennie van Vuuren noted in their book Devil in the Detail: How the Arms Deal Changed Everything.

But Manuel eventually turned from resistor to defender, attacking the standing committee on public accounts (Scopa) and the auditor-general after Scopa got the go-ahead from Parliament to launch a full-scale investigative and forensic probe into the deal, according to Holden and Van Vuuren.

Arms deal activist Terry Crawford-Browne also contends that Manuel – who, he asserts, should be investigated for perjury and money-laundering in relation to the deal – “must take responsibility for his failures”.

Acknowledging that Manuel was “was initially opposed to the deal on the basis of SA’s other more urgent priorities”, Crawford-Browne believes that he caved in to “political pressure from Mbeki and others”.

“The arms deal supply contracts were signed on 3 December 1999, subject to finalisation of the loan agreements by the minister of finance. He signed those agreements on 25 January 2000 despite warnings that allegations of corruption had been forwarded to Judge Heath for investigation, and that it would be fraudulent to proceed with financing until Heath had made his determinations,” Crawford-Browne insists. “Manuel went far beyond his borrowing authorities.”

While Manuel – who has slammed Crawford-Browne’s assertions as “without moorings in facts or reality” – has never spoken in detail about the deal, Pippa Green revealed in Choice Not Fate: The Life and Times of Trevor Manuel that treasury officials felt a “sense of discomfort throughout”.

“But suspicion is not the same as proof and in the end treasury officials and Manuel had to accept that it was Mbeki’s prerogative to push the deal forward,” Green wrote.

Passing the buck

Kasrils, who has become a strident critic of Zuma’s scandal-ridden government, might also be ruing his defence of the deal. The then-deputy defence minister was one of its staunchest champions, telling a convention of international and local arms in 1998 the selection of the preferred bidders could stand up to the “closest scrutiny”.

Kasrils and then Denel deputy CEO Max Sisulu also launched a R1.8-million defamation lawsuit in 2001 against four newspapers that reported that they were among senior ANC officials being probed for corruption in the deal.

Writing in American political newsletter Counterpunch two years ago, UKZN Centre for Civil Society director Patrick Bond recounted how Kasrils defended the deal in 2012. When taxed by an anti-corruption campaigner on how he could sleep at night, Kasrils responded that he was sleeping well because as far as he could tell, “the arms deal didn’t corrupt at ministerial executive level in major transactions” though he conceded that at “secondary level, the company-to-company transactions had plenty of holes”.

While it is unclear how Manuel and Kasrils view the deal now, Lekota is definitely singing from a different hymn sheet. Lekota, who was defence minister at the conclusion of the package, rejected outright allegations in 2007 by Independent Democrats leader Patricia de Lille that the ANC and the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund benefited inappropriately from the deal.

“She can’t come and use the House of Parliament to make allegations against instances… who are innocent, who cannot speak in this House,” the then-ANC chairman said emphatically at the time. “Therefore I reject with contempt these assertions she’s made.”

But last year upon being subpoenaed to appear before the Commission, Lekota – who left the ANC in 2008 to form the Congress of the People – claimed he was the wrong person to interrogate as he had neither been accused nor had knowledge of any corruption relating to the deal.

“I joined the subcommittee when I became Minister in 1999, and by that time everything had been done and I only had to sign it off. However, Jeff Radebe was there from the beginning to the end yet he has not been called to testify. President Zuma has been implicated in the deal and avoided trial, but he has not been subpoenaed. How did that happen,” he told the Sunday independent in September 2013.

How did that happen, indeed? How did the arms deal happen? That is what South Africans are hoping Manuel, Kasrils and Lekota will tell them in the coming days.