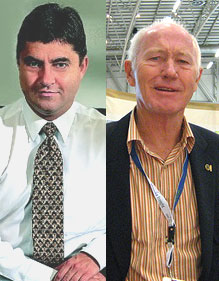

Their breadth of recall is mind-boggling. Dates, figures, names and irregularities that several official investigations have tried – unsuccessfully – to unravel for over 15 years, these are the details that arms deal activist Terry Crawford-Browne and whistleblower Richard Young readily have at their fingertips.

It’s not surprising, though, as both have spent the last 15 years getting to grips with the arms deal, using their own money, time and energy.

It was in fact peace activist Crawford-Browne’s pursuit of the truth which led to the establishment of the Seriti Commission of Inquiry into the arms deal. He approached the Constitutional Court in October 2010 asking it to direct President Jacob Zuma to appoint an independent judicial commission of inquiry into allegations of wrongdoing in the arms deal or to require him to reconsider his refusal to do so. In September 2011, Zuma finally announced he would institute a commission … and so the Seriti Commission was born.

The decision was vindication for the now 71-year-old champion of the underdog who had spent 12 years battling to unearth the truth, a quest that has bankrupted him and left him to rely on his long-suffering but supportive wife Lavinia.

But Crawford-Browne is not celebrating his pyrrhic victory. He will not stop, he says, until the government apologises to the people of South Africa, until the arms deal is cancelled because of the fraud and corruption it involved, and until the estimated R70-billion that was spent is reimbursed and redirected to alleviating poverty.

“The arms deal has unleashed the culture of corruption and cover-up that has become normal in South Africa,” says Crawford-Browne.

Not backing down

Young supplied the compelling factual affidavit for Crawford-Browne’s Constitutional Court challenge. He, too, is determined that the international supplier companies involved in the arms deal – the “perennial corrupters”, as he terms them, who take “absolutely massive” amounts of money away from Africa – be brought to book, along with the local transgressors. Companies implicated, like Ferrostaal, Thales, Thyssen, British Aerospace and Saab, should “feel the heat” of formal sanctions, he told Noseweek last December. “These companies are even prepared to pay multi-billion-rand fines for what they do.”

Young became a whistleblower after his company, C²I² Systems, was dropped despite having been initially selected to supply the information management system for the German-built corvettes. He won a R15-million payout for damages in 2007 after a long battle, but is determined to continue fighting for the entire truth to be revealed.

“I’m on an anti-corruption campaign because as much as I dislike the negative parts of the country, I’m a true South African and I know that corruption will stuff it up.”

Although Young has spent millions of his own money as well as years of his life in pursuit of the truth, and has also lived in fear for his life, he remains determined to expose the truth.

He also wants to encourage whistleblowing in South Africa, a right enshrined by law. “I want others to see what I’ve been able to achieve with regards to the arms deal. I want people who know more about, say, electricity corruption or health care, oil or gas corruption, or cellular telephony – any corruption, whatever it is – to make that their hobbyhorse, to take it on and not let it rest,” he told Noseweek.

Unconvinced by the Seriti Commission

Not letting something rest is what Crawford-Browne does all too well.

The former banker was the Anglican Church’s adviser on the defence review in the mid-1990s when he “began to hear rumours in 1998” of “R25- to R30-million transferred by (British arms manufacturer) BAE as bribes to ANC politicians”. After getting confirmation of the payment from Sweden, Crawford-Browne got Britain’s Metropolitan Police to investigate with the help of Campaign Against Arms Trade. However, “to his astonishment”, he was informed that it was then not illegal in English law to bribe foreigners and therefore there was no crime to investigate.

That set him on his quest to get to the bottom of the deal, a journey which has seen him take on former finance minister Trevor Manuel in the courtroom as well as prevail on former president FW de Klerk and Archbishop Desmond Tutu to appeal to presidents Kgalema Motlanthe and Zuma to appoint a judicial commission of inquiry. He got nowhere until his application to the Constitutional Court in 2010.

But having succeeded in getting the commission instituted, Crawford-Browne is now calling for it to be terminated. He describes it as a “farce”, saying that “It has failed to do what it could have done.”

Young too is deeply ambivalent about the commission, even though he concedes it has already exposed “massive revelations” which have not been properly grasped by ordinary South Africans.

One revelation was the admission of a top Armscor official that there was a “deviation” from standard policy procedure, a complete u-turn on his testimony under oath 12 years ago that the deal had been conducted within the company’s normal procedures.

And recently, former trade and industry minister Alec Erwin admitted the offset programme, designed to yield economic benefits from foreign investments, had not been a total success. With hindsight, Erwin conceded, the government would have done things differently in trying to create economic growth through the 1998 arms deal.

The about-turn of Armscor at the commission, says Young, is “proof that the arms deal, each leg of it, was done unlawfully.”