|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

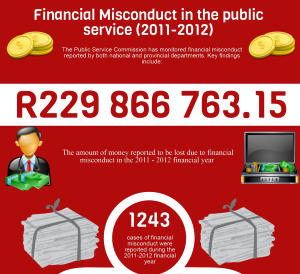

The Public Service Commission (PSC) has submitted to Parliament its annual fact sheet on finalised cases of financial misconduct, from national and provincial government departments, for the 2011/2012 financial year.

The Public Service Commission (PSC) has submitted to Parliament its annual fact sheet on finalised cases of financial misconduct, from national and provincial government departments, for the 2011/2012 financial year.

The PSC, a government organisation that investigates, monitors and evaluates the organisation and administration of the public service, has been tracking such finalised cases since the 2001/2002 financial year. The report forms part of its operating mandate, which stipulates that it must report annually to the National Assembly, as it is accountable to this body.

It must also report to the legislature of the province concerned on its activities in each province.

Striving for a transparent public service

The PSC says that bringing cases of financial misconduct to a conclusion is a key component of a transparent public service.

In the 2011/2012 report, the PC revealed that 1 243 financial misconduct cases were reported – 660 cases, or 53% from national departments and 583, or 47% by provincial departments.

The total sum of money involved stands at R230-million, which resulted from unauthorised, irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure.

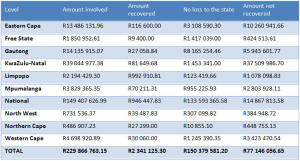

The breakdown between the national and provincial departments is summarised in the chart below.

Reports submitted by national and provincial departments indicated that R2.3-million, or 1.1% of the total, was recovered from employees found guilty of financial misconduct, and R150-million, or 65.4%, was considered as no loss to the state. An amount of R 77-million, or 33.5%, was not recovered.

Reports submitted by national and provincial departments indicated that R2.3-million, or 1.1% of the total, was recovered from employees found guilty of financial misconduct, and R150-million, or 65.4%, was considered as no loss to the state. An amount of R 77-million, or 33.5%, was not recovered.

Taking action

At national level, R149-million was involved, of which 66.9% or just over R100-million, was reported by the Department of Human Settlements. Most of this sum was related to a case involving a contravention of section 38 (1) (n) of the Public Finance Management Act, said the PSC.

The department with the second highest reported figures was the Department of Home Affairs with R12-million. The Department of Mineral Resources reported the lowest cost of just under R5 500, or 0.003%.

In the provinces, the amount involved in financial misconduct was R80-million. KwaZulu-Natal submitted the highest figures of R39-million or 48.5%, followed by Gauteng at R14-million or 17.6%. The lowest figures came from the Northern Cape, which reported the relatively small sum of R487-million, or 0.6%.

In the provinces, the amount involved in financial misconduct was R80-million. KwaZulu-Natal submitted the highest figures of R39-million or 48.5%, followed by Gauteng at R14-million or 17.6%. The lowest figures came from the Northern Cape, which reported the relatively small sum of R487-million, or 0.6%.

There were 305 instances, out of the 953 cases in which employees were found guilty, where criminal cases were instituted against employees caught red-handed.

In 263 cases, departments indicated that no criminal proceedings were instituted because the criminal activities didn’t warrant such legal action, while in 384 cases, departments failed to indicate whether criminal proceedings were instituted.

The PSC concluded by saying that the numbers of public officials that commit and get charged with financial misconduct is increasing “at an alarming rate”. Although the amounts involved decreased, compared to the 2010/2011 report, the number of employees charged with financial misconduct in the 2011/2012 financial year has increased by 25%.

It recommended that departments install control systems to prevent financial misconduct.

An alternative view

However, this may not be as rosy as it looks, says forensic investigator Peter Allwright, a specialist in the field of white-collar crime.

In an interview with Business Day, Allwright remarked that firstly, the report only dealt with finalised cases, so any cases that have been delayed, have not yet commenced, have been suspended or are being appealed are not part of the equation.

Also, he said, the number of employees that are found guilty but are still employed, stands at 76.5%. "Only 23.5% of officials found guilty of financial misconduct are discharged.”

Allwright conceded that many cases did not warrant dismissal, but still, the trend is for officials found guilty of serious acts of financial misconduct to keep their positions.

The reason for this, he said, could be because government officials are finding corruption harder to nail down than straightforward theft.

"My experience has shown that most law enforcement officials try to convert a corrupt offence to a theft offence because they don’t comprehend the key elements of corruption and find the simple ‘take and run’ concept of theft simpler to comprehend, investigate and prosecute.”