Democracy: from Ancient Greek dēmokratía, dēmos ‘people’ and kratos ‘rule’. Literally, rule by the people, especially rule of the majority. In its basic form, a government in which state power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving free and competitive elections.

September 15 is the International Day of Democracy. The day was first proclaimed on 8 November 2007 with resolution A/RES/62/7 issued by the UN General Assembly a full 10 years after the adoption by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) of a Universal Declaration on Democracy. That declaration affirms the principles of democracy, the elements and exercise of democratic government, and the international scope of democracy.

Led by the Qatari delegation, which drafted the text of the resolution, the UN General Assembly agreed to observe 15 September as the International Day of Democracy. The date is significant in that it marks the very day that the IPU, a decade before in 1997, adopted its Universal Declaration on Democracy.

Thus, 15 September provides an opportunity to celebrate democracy, and to assess to what extent the principles of democracy are promoted and upheld around the world. It is a pressing reminder that the need to promote and protect democracy is as urgent now as ever.

This year’s theme is Navigating AI for Governance and Citizen Engagement, and it focuses on the importance of AI as a tool for good governance.

“Left unchecked, the dangers posed by artificial intelligence could have serious implications for democracy, peace, and stability,” says UN Secretary-General António Guterres in his message for this year. “This can start with the proliferation of mis- and disinformation, the spread of hate speech, and the use of so-called deepfakes.”

Yet, Guterres continues, AI has the potential to promote and enhance full and active public participation, equality, security, and human development.

“It can boost education on democratic processes, and shape more inclusive civic spaces where people have a say in decisions and can hold decision-makers to account.”

These are, of course, basic tenets of democracy and it is interesting that AI is being thought of as a tool that can enhance democracy – and why not? Provided, of course, that there is effective governance of AI at all levels, including internationally, Guterres says.

He mentions the interim report released a few months ago by the High-Level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence, titled Governing AI for Humanity. “The message is clear: AI must serve humanity equitably and safely.”

Why is democracy important?

In a nutshell, democracy promotes equality in societies.

The preamble to that UN resolution of 2007 states that “while democracies share common features, there is no single model of democracy” and that ” democracy is a universal value based on the freely-expressed will of people”. And while there are as many variations of democracy as there are definitions of the concept, the set of common features is consistent:

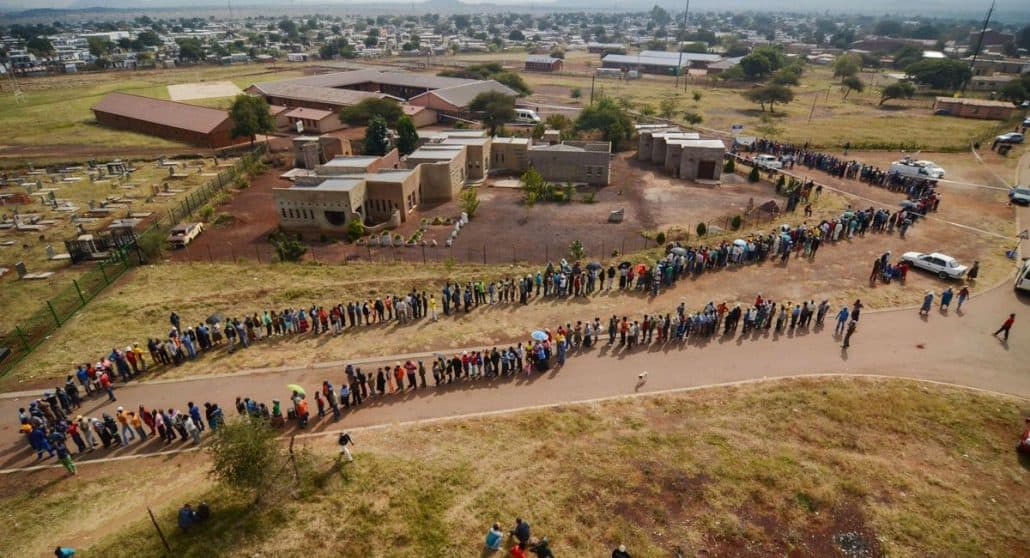

- Free and fair elections:

While voting is an important tool for change, it is not the only one, nor is it enough, says Corruption Watch board chairperson Themba Maseko. “Demanding better services and holding accountability must continue beyond election day … Citizens cannot afford to outsource their future to a handful of elected individuals and not hold them accountable for addressing the crises that are engulfing our country.”

- Universal suffrage:

The right for people to vote, as many as are answerable to a specific country’s laws. For instance, in many countries only people aged 18 years and older can vote, while some nations allow prisoners to vote and others don’t.

- Rule of law:

This principle ensures that no one is above the law, including government officials – but its successful implementation requires an independent judiciary, transparent legal processes, and equal application of laws. Some democracies – such as South Africa – have constitutional courts to ensure laws and processes align with their constitutions.

- Protection of individual rights and freedoms:

Most democracies uphold core freedoms, but the extent can vary from government to government. For example, freedom of speech has different limitations in different countries, particularly regarding hate speech or defamation. Some democracies have these rights enshrined in a constitution, while others rely on statutory law.

- Separation of powers:

The classic model separates executive, legislative, and judicial branches, but again, implementations differ. Parliamentary systems may have closer ties between executive and legislative branches compared to presidential systems. Some countries add additional checks like independent central banks or anti-corruption agencies.

- Multi-party system:

While most democracies have multiple parties, the number and strength of parties vary greatly. Some countries have two dominant parties, while others have many significant parties. Electoral systems can influence this – proportional representation often leads to more parties in Parliament than first-past-the-post systems.

- Civic participation:

Beyond voting, this includes the right to protest, petition the government, and engage with or work for civil society organisations. Some countries have mechanisms for direct democracy like contributing to policy and law development, or taking part in referendums.

- Transparency and accountability:

This involves the existence of freedom of information laws, financial disclosure requirements for officials, and mechanisms to investigate and sanction government misconduct. Some countries have ombudsman offices or special prosecutors to enhance accountability.

- Independent judiciary:

While most democracies strive for judicial independence, appointment processes vary. Some use non-partisan commissions, others involve legislative approval, and some even elect judges. The power of judicial review – the ability to strike down laws as unconstitutional – also varies between systems.

- Peaceful transfer of power:

This is crucial for democratic stability. It requires losers accepting results and winners respecting the rights of the opposition. Some countries have formal transition periods, while in others, power changes hands immediately after elections.

Echoing these principles, Resolution 62/7 is mindful of “the central role of parliaments and the active involvement of civil society organisations and media and their interaction with governments at all levels in promoting democracy, freedom, equality, participation, development, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law”.