|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Kavisha Pillay

First published on Maverick Citizen

In October 2020, the National Treasury launched a public dashboard of all Covid-19 expenditure reported to it by national, provincial and local government departments. This data, though incomplete and inaccurate in some instances, has made it possible to understand how much each department spent, the items procured and the suppliers who got the tenders.

Corruption Watch has analysed the spend by the South African Police Service (Saps) and the results reveal a disturbing trend of gross inflation of prices, fruitless and wasteful expenditure and possible corruption.

Since the start of the pandemic, Saps has spent R1 561 202 820.76 on PPE, sanitisers and disinfectants, and other items. Of this expenditure, 56% was for surgical masks, 32% for hand sanitisers and disinfectants, and the remaining 12% for goggles, surgical gloves, thermometers, fogging of buildings and so on.

Hand sanitisers and disinfectants

In a series of articles, Maverick Citizen exposed the questionable dealings between the Saps and Red Roses Africa — a Mpumalanga-based company that scored close to R500-million to supply hand sanitiser and disinfectants to police stations across the country. This is now under investigation by the Special Investigating Unit and the Competition Commission.

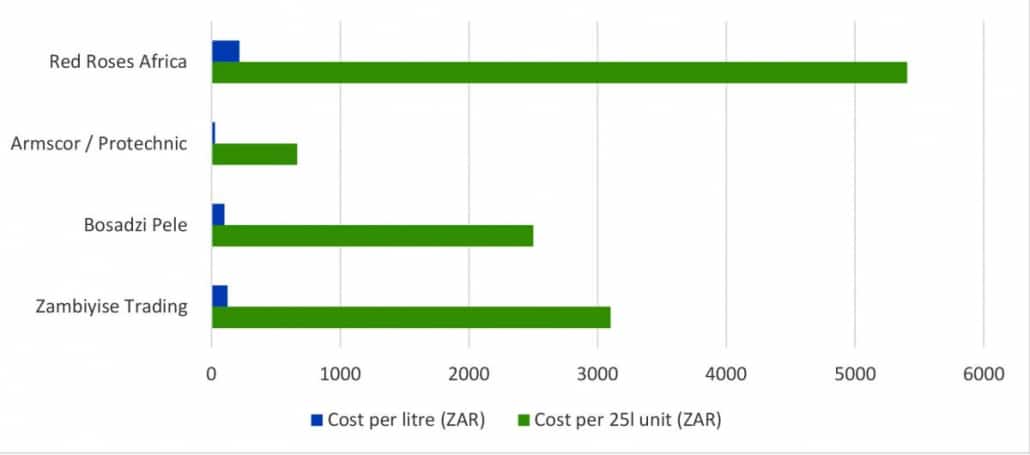

SAPS sourced 90 000 x 25-litre measures of hand sanitiser and disinfectants from Red Roses Africa, which charged R5 405 per 25l unit, resulting in a payment of R486 450,000.

Cleaning industry experts estimate this is a mark-up in excess of 600%; they point out that “the manufactured cost of 1 x 25l container of the best quality Quaternary Ammonium Compound (QAC) is around R500.” They say that Red Roses Africa very likely purchased the disinfectant from a contract manufacturer of disinfectants. If the contract manufacturer’s markup on 90 000 containers was say 50% or R250, this would mean that Red Roses Africa would pay in the region of R750 per 25l unit. In that case, say the industry experts, “The percentage markup calculation to get to the R5 405 would therefore be 620%.”

If this calculation is correct, it is a hefty profit indeed and certainly something the Competition Commission would be compelled to investigate.

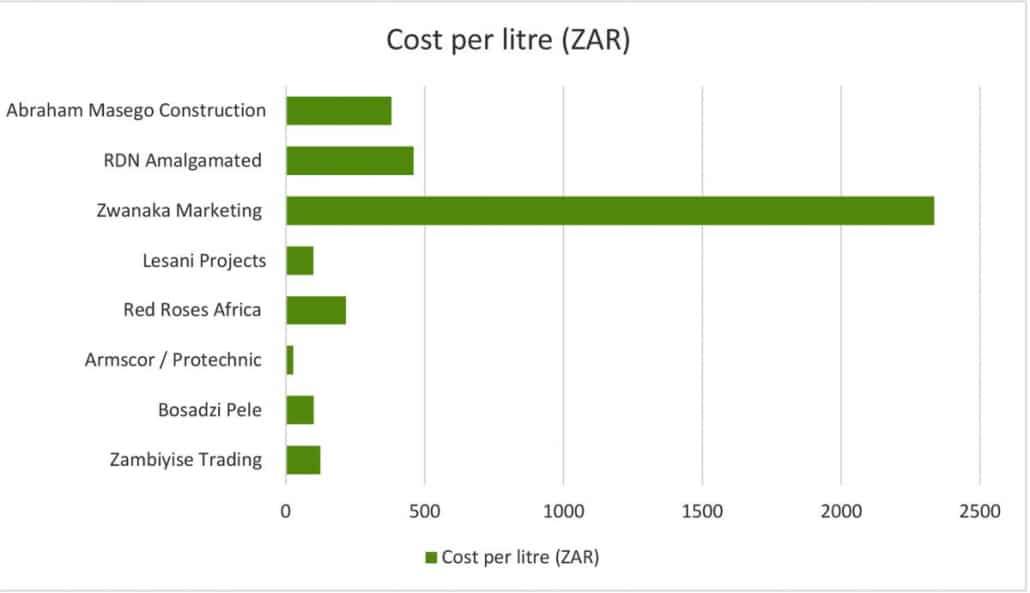

But while Red Roses Africa earned almost half a billion rand on the tender owing to the quantity of the purchase, a comparison on the price per litre of hand sanitiser/disinfectant reveals that they weren’t the most expensive supplier.

If the Treasury figures are accurate, then Zwanaka Marketing charged R2 335 per litre, RDN Amalgamated charged R460 per litre and Abraham Masego Construction charged R380 per litre. The Saps purchased relatively small quantities from these three suppliers, but it is important to note the gross inflation of prices.

Masks

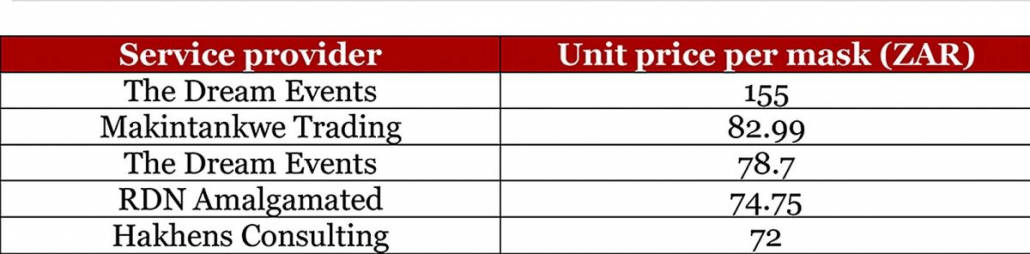

In the period between March and May 2020, the Saps procured 43 559 996 masks — enough to give at least one mask to 72% of South Africa’s population. Prices varied, with the lowest service provider charging R9.50 per mask and the highest service provider, The Dream Events, charging R155 per mask.

According to the dashboard, the Saps purchased 10 000 masks from The Dream Events at R155 per mask, and a further 8 500 masks at R78.70 per mask, resulting in a total payment of over R2.2-million for 18 500 masks. If the Saps had purchased the same number of masks at the lowest rate charged (R9.50), the total amount paid would have been R175 750 — saving the taxpayer R2 044 008.

Gloves and other PPE

The dashboard lists the Saps’s purchases for “non-sterile examination gloves” which are generally used for non-surgical medical procedures or examinations. These items are relatively cheap, with some service providers charging the government R1 per pair of gloves.

However, Zwanaka Marketing and Zambayise appear to have charged the Saps R350 and R222 respectively, for a single pair of non-sterile examination gloves. In these instances, the Saps paid more for non-sterile gloves than they did for sterile gloves, which are specialised and more expensive. Again, although the quantities purchased are relatively small, a combined order of 900 gloves resulted in a payment of R251 000. If this was purchased at the lowest price, Saps would have only paid a total of R900.

Another questionable transaction listed on the dashboard is the purchase, for just under R50-million, of items called “wipes containers”, which are assumed to be plastic dispensers for wet wipes. Suppliers charged Saps between R480 and R750 for one container. A basic internet search reveals that the retail prices on these wipes containers range largely between R45 and R200.

Conclusion

The trends emerging from the Saps expenditure data are by no means unique to the institution and have most likely occurred across departments and in all levels of government. The Saps spent more than R1.5-billion on PPE during the pandemic, but we cannot be sure that the institution got value for money on the items purchased, or if these items were in fact delivered.

We must also question the vast quantities purchased by the Saps and how these items are being used — or if there are possibilities that the goods are being resold into the marketplace. According to Corruption Watch data, this is fairly common practice for the Saps, which is accused of reselling confiscated goods such as alcohol and contraband, as well as other items.

Beyond the spending patterns, the data also reveals abuse of supply chain processes, and accounting officers — who are meant to exercise oversight — approving payments that were grossly inflated above the market-related value. Furthermore, the analysis brings under the spotlight companies who have put profit over people, during a deadly pandemic, and crudely and shamelessly inflated their prices for basic items such as gloves and masks. These companies, it can be argued, should be fined, penalised or prevented from doing business with the state in future, because of their bad-faith tactics.

Last, efforts such as the publishing of Covid-19 expenditure are important for promoting transparency in procurement processes. But if no accountability ensues following the disclosure and analysis of this information in both the public and private sector, it would be yet another fruitless intervention.