First published in City Press

Until it becomes “embarrassing to be caught with one’s hand in the cookie jar”, South Africa is never going to beat corruption.

This is according to a Durban civil servant, who’s among the 70% of South Africans who don’t believe we’ll ever stop corruption, new research by think-tank futurefact has revealed.

Claire Shortt (32) lives in Cape Town’s southern suburbs and says South Africans are “used to” corruption.

“We have resorted to sticking our heads in the sand and pretending it’s not happening – or at least, believing we can’t make a difference. How do we as regular South Africans hold those in power accountable? Raising concerns in the media hasn’t worked. Protests don’t work. Policing bodies such as the Scorpions and the Hawks haven’t worked.

“Where do we go next? Perhaps someone like Thuli Madonsela can make a difference – but we’d need to clone her 1 000 times over if we want to stamp out corruption in the very long term.”

Durbanite Sandile Mtimkhulu (33) says he’s exposed to corruption every day. “Corruption is rife in government institutions. I work for government and I always talk to people, and I know these things. Officials are always discussing how they can fleece government.

“I also know some auditors who cooked municipal books, and extorted money from municipal managers and mayors in exchange for favourable financial statements.”

We need a strong culture of good ethics

The problem, according to the administrator in the labour department, is that government is reactive when it comes to tackling corruption. “There are no risk management tools to pick up possible corruption.”

He also believes government departments and private companies need to instil a culture of honesty and integrity, where corruption is frowned upon. “It should be embarrassing to be caught with one’s hand in the cookie jar.”

Thokozani Nkosi, a librarian from Snake Park in Soweto, says he experiences corruption all the time.

“Sometimes it’s very subtle and you don’t think of it as corruption. Recently, I visited the traffic department and I forgot my keys at the counter. When I went back there, a traffic officer who had picked them asked for a ‘cold drink’ [code for a bribe]. A few weeks ago, I had to change the ownership of a car I had bought and the officer who assisted me also asked for a ‘cold drink’.”

Nkosi (35) says we have to tighten the laws that deal with corruption because right now, people might think it’s pointless to report their experiences because nobody gets punished.

He wants government to set up an independent crime-busting unit.

Government talks too much, acts too little

But corruption busters say we shouldn’t give up – even though they admit there’s not much political will to stop corruption in its tracks.

Jay Kruuse is the executive director of the Public Service Accountability Monitor, which is based at Rhodes University in Grahamstown. “The norm is that corruption is tolerated. We are at a tipping point and scandals like Nkandla will define our democracy. We require bold and principled leadership in the fight against crime.”

Kruuse says no country can completely eliminate corruption, but it can be managed.

“We need to strengthen Parliament’s oversight. The Hawks should be independent in order to curb high-level crimes. We have to make them most potent. As it is, the Hawks have brought very few cases to court using the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act.”

Lawson Naidoo, the secretary of the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution, says there is “lots of rhetoric about being serious about fighting corruption”.

He adds: “But a lot of politically connected people get away with murder and that undermines people’s confidence in the state. There are no requisite levels of political will.”

Naidoo agrees with Nkosi’s call for an independent agency to fight corruption, particularly in the private sector.

“Currently, we have a number of agencies such as the Auditor-General, the Public Protector, the Special Investigating Unit and the Hawks, most of which look at the public sector. Who is taking care of the private sector? Without an independent agency, we are hopeless.”

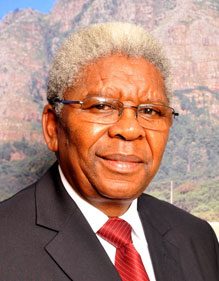

Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Njongonkulu Ndungane, the chairperson of Corruption Watch, is upbeat but warns that South Africans are complicit when it comes to corruption.

“Eliminating corruption is doable. We just need to see it as a cancer that is eating society. Findings of offices such as the Public Protector and the Auditor-General should be taken seriously,” he says.