|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Although the basic right to sufficient water is enshrined in South Africa’s Constitution, gaining access to that clean water has been a long struggle for millions of people. The struggle is still happening, and it’s a crucial driver of uprisings in South Africa today.

Although the basic right to sufficient water is enshrined in South Africa’s Constitution, gaining access to that clean water has been a long struggle for millions of people. The struggle is still happening, and it’s a crucial driver of uprisings in South Africa today.

A 2012 study by the South African Water Research Commission confirms the link between water scarcity and civil unrest.

Why are people dissatified, when the 2011 national census revealed that 91% of South Africans had access to improved sanitation and an improved water source, with 73.4% supposedly having piped water right inside their dwelling or on their premises?

Part of the answer has to do with corruption, and it's an important part, if reports submitted to Corruption Watch, and regular newspaper reports, are anything to go by.

Corruption swallows up huge amounts of money every year – the numbers may vary but the word “billion” crops up often. In 2011 the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution said that an estimated 20% of the country’s annual GDP is lost to corruption. In the same year the head of the Special Investigating Unit – mandated to “recover and prevent financial losses to the state caused by acts of corruption, fraud and maladministration” – presenting the body’s annual report, estimated that a R30-billion sum that was unaccounted for was “not unrealistic”.

Communities often express their unhappiness and frustration with poor service delivery, lack of access to water, maladministration, and corruption through protests, which have been occurring regularly across the country. Several people have died as a result of ensuing violence, but substandard facilities have also claimed lives.

Who are the culprits?

Responsibility for providing water services is shared by several government entities. On the one hand, the country’s 231 municipalities are responsible for the provision of water and sanitation services. This may be accomplished with the help of private companies or municipally owned entities to perform tasks such as water treatment.

Policy on water is set by the Department of Water Affairs, and dams and other major water-related infrastructure are managed by the water boards.

However, most of our reports are linked to corruption at the municipal level.

With reports of corruption and poor service delivery hitting the press on a regular basis, access to water is a contentious issue that has sparked desperation, violence and death. In this election year people want to know what the government plans to do to address the situation.

Reporting water-related corruption

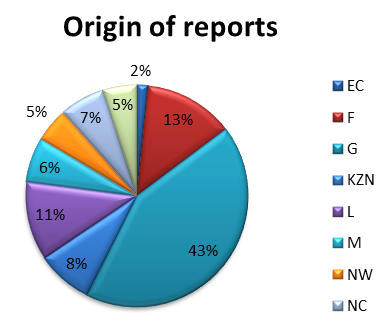

Corruption Watch has received 62 reports of corruption related to water between January 2012 and December 2013 – most of the reports (43%) originated in Gauteng province, followed by 13% from the Free State and 11% from Limpopo.

Not surprisingly, 50% of all reports around the country originated in small towns – the exception is Gauteng province where 80% of reports came from metros.

Only in Gauteng (21), KwaZulu-Natal (four), the Western Cape (two), the Free State (two) and the Northern Cape (one) were there any reports from major metropolitan areas, including provincial capitals.

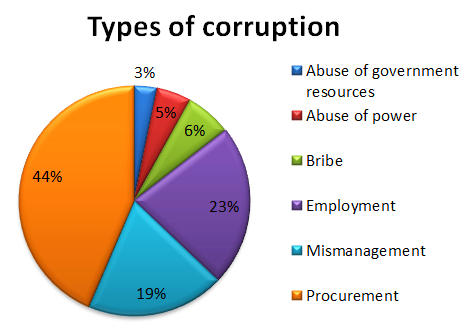

Our reports reveal that the most commonly named type of corruption is that linked to tenders or procurement – 44% of all reports were of this nature. Other types of corruption reported relate to bribery, mismanagement, abuse of power or resources, and employment – the latter is the second most commonly reported type of corruption.

Reporters allege that tenders are awarded to friends and family, and that more often than not this involves infrastructure – repairs to pipes or construction related to the laying of new pipes.

“XXX munisipality awarded 2 million tender for fencing without following tender process , no need for fence old one were stil good ,urgent need for water road repairs medical and water supply in comounity yet money can be wasted to enrich tederpreneurs who are friends with right people,” alleged one reporter from Limpopo.

In a few instances, where the whistleblower is identified as a municipal employee or official, whether of the municipality itself or the water entity within the municipality, the nature of the tender is not specified but it’s merely stated that it has to do with water affairs.

Most of the reported corruption is linked to municipalities – only four reports were received in relation to provincial or national departments of water affairs.

In terms of employment, 23% of reports were related to this situation. Specified corruption includes nepotism and the employment of officials who are not qualified for the position. Reporters also indicate irregularities in the employment process – for instance, that the post was never advertised.

A Northern Cape reporter described the situation thus: “The New Regional Manager of XXX Water has mislead the Acting CEO and the Former Board into appointing.He has lied about his management experience and does not have an ECSA Registration required by the adverisement. Word is that he does not even have those management qualities that are required for the post. His references are his close associated and they lied for him.”

The 19% of reporters that were concerned about mismanagement claimed that it led to inadequate supply or quality of water.

And in terms of bribery, this took the form of payment for an illegal connection to water, or paying for a service that is actually a right. One reporter said that in order to get her water reconnected she had to pay a bribe, even though she was entitled to the water being connected.

“The water supply to my property was disconnected by an agent of the City of XXX on 6 June 2013. The agent told my domestic worker that he would reconnect the water for a fee of R100. I refused and immediately paid the outstanding amount to the City of XXX. I was told that it would take 48 hours for my water to be reconnected,” a reporter from a Gauteng metro said, adding that six days later there was still no water.

By then the family was desperate, the reporter said, so “my domestic worker then called [the agent] to request him to reconnect the water. He arrived at the property, took the bribe, assured my domestic worker that he was not doing anything illegal, and reconnected my water.”

So what are the numbers?

Over the past few decades, access to water for South Africans has improved – but not as much as could be expected, given the timeframe.

The first democratically elected government inherited a situation where millions of people had little or no water and sanitation services. Back then there was apparently some political will to address that situation – who can forget then president Thabo Mbeki, in his 2004 State of the Nation speech, talking about the government’s “long-term objectives such as the provision of clean running water to all households by 2008, decent and safe sanitation by 2010 and electricity for all by 2012”?

But the government has not made good on its promise, although there has been some improvement.

According to the WHO/Unicef’s global Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP), which takes data from surveys and censuses into account, the share of the population with access to an improved water source increased from 83% in 1990 to 91.5% by 2011. The number of people benefiting increased from 30.3-million to 46.2-million.

In terms of sanitation, the JMP estimates that progress has been slower. The percentage of South Africans with access to improved sanitation increased 64% in 1990 to 75% in 2011. The numbers increased from 23.5-million to 37.3-million. The census figures tell a different story – they claim that access to sanitation increased from 83% in 2001 to 91% in 2011 and that 53% of households had flush toilets in 2001, whereas 60% had this facility in 2011. The figures are different because the JMP doesn’t include shared facilities in its definition, whereas the census does.

The JMP’s data indicates that in South Africa in 2011, there were still some 13-million people without access to improved sanitation, and 4.3-million people that do not have safe drinking water.