|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Sabeehah Motala

First published on News24

In just one day, South Africans who have registered to vote will be making their way to their local polling stations, ready to have their say in who leads the country for the next five years. The track record of corruption in the governments we have elected so far is undeniably problematic, so commitment to rooting out corruption will definitely be a focal point for voters this time around.

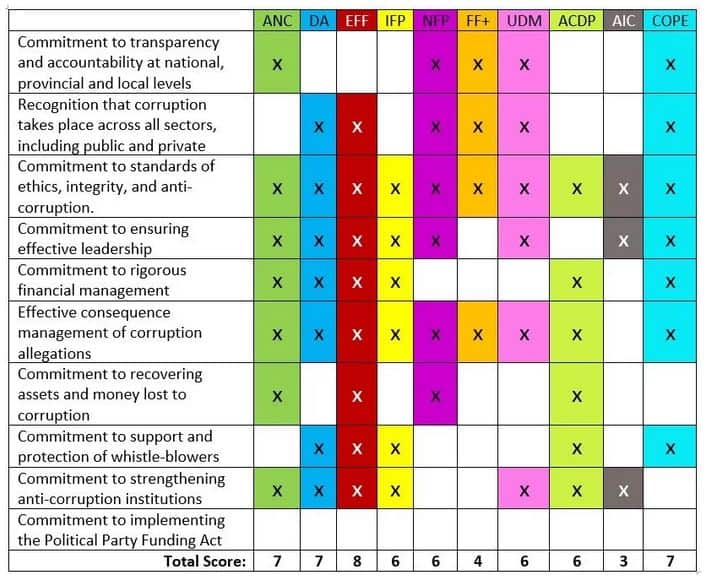

Corruption Watch has highlighted certain anti-corruption commitments that all political parties should ideally be making in their manifestos. These indicators relate to key problem areas that need to be addressed in order to restore good governance, accountability and trust in government. They show how well the manifestos of the current top 10 parties in government recognise, understand and seek to tackle corruption.

What we want from our political parties

Political parties should, first and foremost, be aware that corruption infiltrates all levels of government, from local to national. Though national corruption is often at the fore, tender corruption is rife within municipalities, and provincial governments play a role in managing healthcare and education, which are hugely vulnerable to corruption. It is also essential that manifestos recognise that corruption takes place across all sectors of society, including the private sector. Recognition of all these vulnerable areas will give parties a broad view of where corruption needs to be addressed.

The initial requirement from political parties is that they have a standard to which they hold themselves, which includes ethical practices, a firm stance on anti-corruption, and commitment to integrity. These standards can then be implemented when selecting leaders of key institutions, and they can be used to hold these leaders accountable.

Equally important in fighting corruption in government is the ability to keep a firm grip on finances, to accurately track how the millions and billions of rand move. In addition, previous administrations have arguably not established the willpower and capacity to make sure that those who do act unlawfully are held responsible for their wrongdoing. And our diving economy, desperate for resources, could certainly benefit from a commitment to recovering assets and money illicitly accumulated.

For effective consequence management to take place, parties need to commit to ensuring that our anti-corruption institutions are sufficiently strong to deliver on holding government accountable. Those reporting to anti-corruption institutions need to feel safe and supported when they are making disclosures.

Perhaps one of the hottest election topics of 2018 was the Political Party Funding Bill, which has now been signed into law by the president, although he has yet to announce a date of enforcement. This means that the act will unfortunately lend no insight into the funding of political parties contesting the 2019 elections.

However, now that political parties are aware of the legal obligation to disclose certain donations, the transparency of the parties themselves should be a key concern for voters. No party has expressed any intention to comply with this new law, not even the EFF who in their manifesto already seek to improve the law to prevent corporate influence in politics.

People need real ability to hold leaders accountable

Aside from these indicators, other interesting anti-corruption ideas populate the various manifestos. Perhaps most striking is the call for a change to the electoral system itself. Several political parties recognise that the current system does not allow citizens to directly elect their president, as the party deploys its leader.

The DA manifesto calls for direct elections for all political offices, whilst that of the AIC would like an electoral system that is centred on people instead of parties. Cope, too, calls for a system that allows individuals to stand for national and provincial elections. Its manifesto also calls for constituency-based representation, and the UDM calls for a hybrid of both constituency-based representation and proportional representation. The EFF calls for municipal elections to be held at the same time as national elections. Changes to the electoral system are suggested as a means to enhance accountability of individual leaders to the public instead of to their parties.

A further assertion from several parties is that the state needs to change the way it conducts business. Many parties have alluded to the fact that this space is vulnerable to corruption, owing to the lucrative nature of the state contracts. The EFF suggests that to prevent corruption in this area, the use of consultants and project management units should be banned. Internal capacity should be built within government, removing the need to use private companies to fulfil the needs of government. The ANC and EFF both suggest that public officials and representatives should not be permitted to engage in business dealings with government institutions. The NFP also iterates this point, and the AIC suggests that a public works programme should exist to tend to government necessities.

Civil society’s role not recognised by all

An area in which only two of the political parties have encouraged engagement with the state is civil society. The NFP and Cope both recognise the role of civil society as watchdogs over government, and their potential for collaboration in terms of coming up with solutions to ensuring accountability. Cope suggests that a Cope government will empower and support NGOs and civil society to carry out this task.

Another mechanism which may create watchdogs would be for government to create spaces for public engagement with their leaders. Increased access to government would allow citizens themselves to easily question their leaders on commitments that have been made. The only party that has committed to improving how communities can engage with the government is the ANC, who have said they will do so through imbizos and innovative use of information technology. It is often a mammoth task for communities, especially those who are rural and disadvantaged, to meet with their leadership, and for the government to take on the responsibility is a welcome idea.

Perhaps worryingly, certain parties have highlighted immigration as linked to corruption, though in different ways. The DA’s approach is that corruption is causing high levels of undocumented people in South Africa, and that asylum seekers are often exploited within the improperly administrated Home Affairs department. The FF+ phrases the sentiment slightly differently, saying that corruption is a factor in the large number of illegal immigrants in South Africa, who do not have anything to offer our country.

The AIC, too, takes quite a negative stance, saying the corruption must be rooted out at our borders, through methods including increased policing and repatriation of undocumented persons. Both the AIC and FF+ seem to react negatively not to the corruption in immigration, but to the undocumented persons themselves, a dangerously xenophobic view.

The FF+ also reacts negatively towards land reform, which is something that the new government will have to preside over. They dismiss it as an issue that the government should be wary of participating in, as it is a breeding ground for corruption.

Building a societal culture of anti-corruption

What is true of all these views, however problematic, is that anti-corruption commitments implemented by parties in government will ultimately influence society. It is therefore important for government to recognise society at large as stakeholders in the fight against corruption. Several parties mention the importance of building a culture of anti-corruption and integrity in society. The ANC manifesto speaks of a “social compact” which will encourage people to speak out against corruption.

The UDM recognises the importance of the “moral compass” of the nation. The ACDP manifesto states that, “Integrity is the internal compass we must all carry,” while the AIC manifesto calls for rights education for members of the public. The Cope manifesto commits to a transformation of South Africa, which requires everyone to commit to personal integrity, trustworthiness and honesty.

Despite all the commitments to anti-corruption, very few give us an idea of exactly how they will achieve certain promises. But is that not the consistent problem with political party manifestos? Most have grand ideas of how to solve corruption, but not many have clear strategies for implementing their goals. The DA is a slight exception, mentioning tactics such as entrance exams for public servants, and introducing an offence for revealing the identity of a whistle-blower. But they too use phrases such as “decisive action” which has yet to translate into anything meaningful.

The only way to find out what this means is to make our mark at the polls, for the party that we consider best capacitated to eliminate the scourge of corruption that plagues our country. Voting lends us legitimacy with which to demand accountability from our leaders.

Be sure that the journey to a more open and trusted government will not end on 8 May. It depends on the will of the people to follow through and ensure that whichever political parties occupy Parliament and legislature are held to the promises they made in their manifestos.

Sabeehah Motala is a project coordinator at Corruption Watch.