Accountability is one of the country’s favourite words at the moment, particularly in relation to the current fast-changing political climate and in the wake of the years of state capture. But accountability means different things to different people, in different contexts. It can be a highly contested concept – so who decides on what counts as accountability, and is it really the magic bullet that it is often made out to be?

Corruption Watch has called for ‘full accountability’ for those implicated in the unfolding Phala Phala matter. But what does this mean? Should President Cyril Ramaphosa resign or be removed? What about Arthur Fraser, the whistle-blower, a man who is not himself untainted by scandal?

Accountability for Corruption Watch (CW) means that the rule of law should be respected and proper processes followed, so that those who are found guilty of wrongdoing receive a just sanction, justly arrived at.

But this is not the whole story, says CW executive director Karam Singh. “There is a substantive and procedural aspect to consider. [The description above] is the procedural aspect. The substantive aspect relates to overcoming impunity, clarifying the obligations of mandate holders, and ensuring there is commensurate consequence management, sanction etc when people do transgress the law.”

In addition, says Singh, there are different standards to which we may hold our leaders – legal, ethical, and more.

So accountability can be a complex issue, one which the Accountability Research Center (ARC) has focused on in its Accountability Keywords Project. The project recently yielded an absorbing paper and discussion on the topic in an attempt to reach common ground in a diverse and challenging field.

“This project addresses ‘what counts’ as accountability, analysing the meanings and usage of both widely used and proposed ‘accountability keywords’ – drawing on dialogue with dozens of scholars and practitioners around the world,” says ARC. “The project includes both an extensive accountability working paper and more than 30 invited posts that reflect on meanings and usage of relevant keywords in their own contexts and languages.”

Download the Accountability Keywords working paper.

Understanding accountability

The ARC is clear that the accountability project’s purpose is not to try to explain how to get accountability, but rather to focus on recognising the many different ways of understanding accountability.

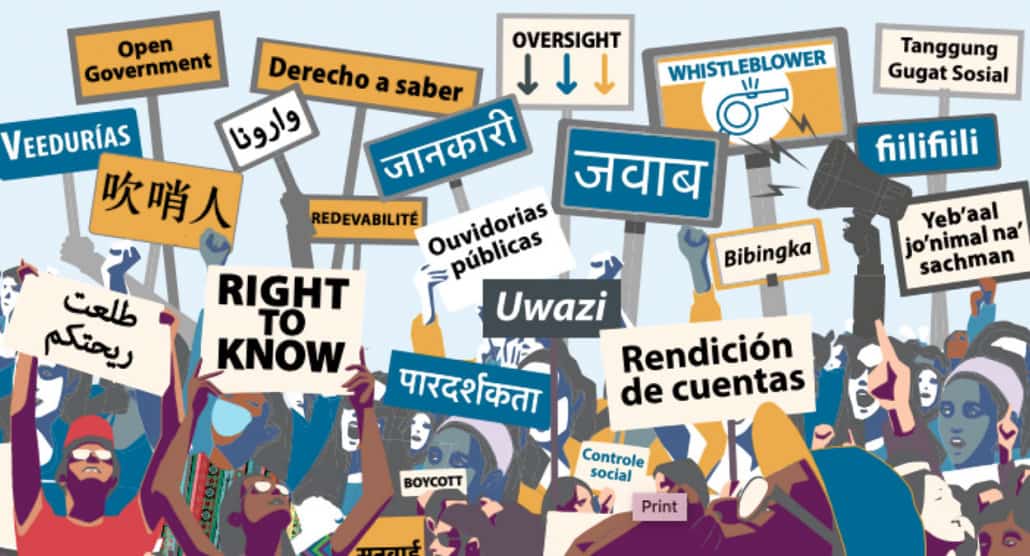

The graphic on the cover of the accountability working paper eloquently explains the diversity and scope of the accountability landscape, as well as the reason for taking keywords from around the world, rather than trying to develop a single definition from myriad versions.

“Keywords incorporate ambiguous and often competing ideas and are sites where global meanings meet local, varied subcultural interpretations …. Keywords chronicle and capture cultural change by creating common categories of meaning against the cacophony of contested local use …”

In the cover image, popular accountability-related words and terms from around the world have been portrayed as placards, ranging from ‘You stink’ in Arabic and ‘Social oversight’ in Brazilian Portuguese, to ‘Answer’ in Hindi and ‘Full transparency’ in Ghanaian Hausa. The paper provides a translation of all terms.

All of them imply condemnation of wrongdoing and an end to opacity and impunity.

Different meanings for different people

Accountability runs from top to bottom and bottom to top, creating what the paper refers to as a “core tension – between accountability to authorities, and the accountability of authorities.” However, it can also run in a side-to-side direction, such as when South Africa’s Auditor-General reports on the performance of other government entities.

And depending on where the demands for accountability are coming from, the scene can look very different. Consider, for instance, police actions to hold law-breakers accountable versus civilian efforts to hold police accountable for soliciting bribes or abusing their authority. Such power relationships involve very different understandings of accountability, especially if possession of the power is unequal.

The police know what accountability looks like for them, as do teachers, or religious leaders. Civilians have their own concept of accountability in relation to police, or politicians, or medical professionals. All these people know it when they see it, says the report, though for all of them it means something different.

It already sounds complicated enough, but there is a further dimension. “The challenges posed by multiple meanings of the same word are magnified when working across cultures and languages. For example, observers have often pointed to the difficulty with directly translating accountability discourse into languages other than English, suggesting that is evidence of the absence of the idea in those cultures.”

However, those claims may be erroneous, because the ways in which accountability is actually communicated in other languages may not be the same as English ways.

“Accountability discourse can be expressed in ways that do not have direct translations.”

The working paper suggests another reason for the challenges in translating the term accountability directly into other languages: because of its fundamental ambiguity in English, which ambiguity is exacerbated by the wide range of people who might seek accountability.

“Those who call for accountability from below can range from citizen, voter, client, consumer, program beneficiary, or investigative journalist to title-holder, survivor, refugee, displaced person, or dissident. Meanwhile, those who hold others accountable from above also range widely, from minister and manager to prosecutor, police officer, faith leader, auditor, tax collector, professor – and dictator, among many others.”

One’s position on the question of accountability will naturally differ depending on which side of the equation one is on. “After all, various kinds of oversight that some would consider to be democratic transparency may look like authoritarian surveillance to others. What some consider to be accountability for transgressions may look like unjust persecution to others. Some focus more on whether rules were followed, while others care more about tangible results.”

Reflecting on keywords in this field, and the diverse vocabulary, helps to provide clarity and understanding on who is accountable to whom, and for what.

What then counts as accountability?

The paper examines this question from three perspectives:

- accountability as a means to address the abuse of power by authorities;

- the difference between authorities explaining their actions and possible consequences; and

- the distinction between the accountability of individuals vs. institutions.

In the first instance, the paper notes a “curious feature of both the scholarly and practitioner fields that address accountability” – both tend to treat public and private sector authorities separately. But this is a false dichotomy, says the paper. “To hold private sector actors publicly accountable often requires government regulation, with enforcement of mandatory standards that address occupational safety, minimum wages, environmental impact, freedom of association, and discrimination based on gender, race, or disability.”

On the other hand, private sector abuses of power are often made possible by complicity with public sector cronies – to avoid regulation and enforcement.

The boundaries of accountability between public and private are therefore fluid and variable. An example of this is provided by the fact that many governments still leave decisions about whether to stop methane leaks in the hands of private companies – which continue to receive government subsidies.

It is important, says the paper, to recognise that the socially and politically constructed boundaries between the two sectors have a strong influence on what accountability looks like.

In the second instance, the question arises as to whether answerability counts as accountability. “The original meaning of accountability in English involves ‘answerability’ – to be liable to account for actions, often involving formal processes that apply specific standards of behaviour or performance.”

In South Africa’s Parliament, for instance, government officials are often expected to explain their actions to various portfolio committees – they answer to the summons but accountability is slow to arise from these hearings, should the officials be found wanting. During the public hearings of the Zondo commission into state capture, former president Jacob Zuma was called on to explain certain matters which implicated him. He refused the opportunity, which did not exempt him from censure in the final report – but as for accountability, that is another matter entirely.

“This raises questions about whether direct answerability is indeed as central to the concept of accountability as many suggest.”

Some people accept answerability as accountability, but others seek more – tangible consequences, including sanctions, remedy, or compensation. “For some, the integral role of sanctions in accountability is commonsensical. For others, including enforcement in the definition sets the bar high and does not acknowledge that answerability processes themselves can count as a tangible consequence.”

If answerability includes actually taking responsibility, including public apologies, then whether and how that is considered justice depends on the social and cultural context. Opinions of and feelings towards South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission differ vastly, depending on which section of the population is being asked.

In the third instance, many governments claim that where abuse or neglect happens, those within the ranks who are responsible will be held accountable. But this requires absolute and undeniable clarity as to who is actually responsible – not always easy to establish.

“The question of institutional vs. individual culpability often comes up when police use obviously excessive force against civilians … whether to focus on individual officers or the police as an institution. In the face of undeniable abuse, institutions prefer to deflect responsibility by distancing themselves from what they claim are just ‘a few bad apples’.”

Sometimes abuses of power happen by design rather than accident – for some governments or companies, corruption is the standard operating procedure rather than the exception, and these cannot be viewed as ‘system failures’ or the work of the aforementioned bad apples.

When entire institutions are called to account, the opportunity arises to implement systemic change – but in the process, individuals who made bad decisions may be let off the hook.

Overlapping concepts

It is equally important to consider what accountability is not.

Accountability is not a synonym for good governance – but it contributes to it. Furthermore, “Poor performance is not necessarily an accountability failure, as long as public officials can be made to answer for it and can face potential sanctions.”

Yet accountability processes are no guarantee of strong performance – South Africans know this very well just by reading the Auditor-General’s annual audit reports on national and provincial government departments, and municipalities, which point out the same failings year after year.

Accountability processes are only effective when they are applied uniformly and without bias, the report notes. In Mexico, top security officials pursued some criminal organisations but not others because those authorities were on the payroll of rival criminal groups. South Africa may be facing a similar situation with recent revelations that gangsters have penetrated to the top levels of Western Cape police leadership.

Neither is accountability a synonym for democracy – because many democracies do not hold themselves accountable to voters or to oversight mechanisms.

“Political democracies may not produce accountability, and accountability processes may exist under less-than-democratic regimes.”

Former president Zuma is a supreme and tragic example of a democratically elected political leader who weakened and undermined institutions that enforce checks and balances.

However, democracy and accountability are undeniably related, especially because “competitive elections are considered to be accountability mechanisms par excellence. If elections are free and fair, they create the opportunity for citizens to express their assessment of incumbents – with consequences.”

Accountability is also not a synonym for responsive governance, although here again there is an overlap. “Responsive governance is widely treated as evidence of accountability … yet responsiveness does not necessarily involve accountability, and accountability does not necessarily involve responsiveness.”

The key distinction between accountability and responsive governance is that responsiveness is at the discretion of those in power, rather than an institutional obligation, says the report. “After all, when under pressure, elites may make partial concessions that involve neither answerability nor enforcement of standards.”

Finally, accountability is not a synonym for responsibility, though they are closely related because responsibility is a prerequisite for applying accountability.

Taking responsibility involves people accepting their agency, whereas holding someone responsible involves answerability to others. People can also evade responsibility by rejecting the principle that they should answer for their actions – however they may not necessarily evade accountability, such as when they are found guilty in a criminal trial after pleading the opposite.