Behind the scenes people have worked for months to establish the structures and rules that inform the way the commission will go about its work. This article is the first in a series that explains the internal regulations and the external procedures and legislation that govern the operation of the commission.

Under Section 84(2) (f) of South Africa’s Constitution, the president has the power to appoint a commission of inquiry in line with the Commission Act 8 of 1947. The Act provides for the president to set the terms of reference of the commission – these indicate its aims and scope. The Commission Act further empowers the president to set regulations, procedures and other powers of the commission. Given the need for expedience that commissions of inquiry generally necessitate, the Act also allows for the president to set a time frame within which the inquiry is to be completed.

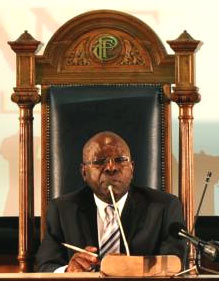

Recently, President Jacob Zuma appointed a number of commissions to investigate matters of concern, including the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Fraud, Corruption, Impropriety or Irregularity in the SDPP, headed by retired Supreme Court judge Willie Seriti. The Seriti Commission, as it is called, has been mandated to look into longstanding allegations of impropriety and corruption within the infamous arms deal.

The Seriti Commission’s mandate

In a proclamation detailing the terms of reference for the commission in 2011, the president mandated the Seriti Commission to investigate and make recommendations on the following:

- The rationale for the SDPP;

- Whether the equipment acquired is being underutilised or not being used at all;

- The degree to which the offsets and job opportunities that were expected to flow from the SDPP have materialised, and the steps to take to realise them if they have not;

- Whether there was any impropriety in the awarding of the contract, either by officials within the government or private persons, and whether this should lead to the cancellation of the deal;

- The ramifications of cancelling the deal.

These terms of reference may be amended or added to from time to time.

The commission is not mandated to institute any legal proceedings if it uncovers impropriety or corruption. It is, however, empowered to make recommendations to the president as to the most appropriate course of action once it has considered all the evidence before it.

To fulfil this mandate, the commission divided its work into phases to help facilitate the arms deal investigation. The first phase involved perusing all submissions made to the commission from parties interested in the SDPP. The second phase – which it is currently busy with – includes public hearings where evidence submitted to the commission in the first phase is heard and witnesses are cross-examined.

The regulations,which were published in 2012, stipulate how the commission deals with evidence and witnesses, including the procedures. They dictate what is allowed and what is not allowed by participants in the commission, thus:

- No person involved in the commission who has gained access to information in the course of the inquiry may disseminate or share this knowledge with any other person;

- Publication, dissemination and inception of any document pertaining to the commission is not allowed without written permission from the chairperson;

- Persons may not insult, disparage and belittle the chairperson or member of the commission, or in any other way aim to prejudice the proceedings in any way.

The regulations also:

- Allow the commission to subpoena witnesses and compel them to answer questions;

- Confer powers on the commission to search and seize documents or other evidence pertinent to the arms deal.

At the public hearings, evidence leaders appointed by the chairperson present the commission with all the pertinent evidence submitted, including leading witnesses in evidence. Witnesses include those persons that had made relevant submissions to the commission, as well as persons who are implicated in those documents.

Witness lists are made available every Friday to all interested parties, and any person may apply to the commission to cross-examine witnesses, or peruse documents presented in witness testimony.

One of the areas in which the commission has drawn criticism, has been with regard to access to documents and cross-examination of witness. In the next part of this series, we examine the offsets associated with the arms deal.

Useful documents:

- Download the Seriti Commission’s terms of reference

- Download the Seriti Commission’s regulations

- Download the Seriti Commission’s directives

- Download the Commissions Act